Introduction

It is universally acknowledged by economists that agricultural shares in aggregate output and the workforce tend to decline as an economy grows. Economists agree, however, only on the existence and inevitability of this phenomenon as a result of general economic growth, while arguing about questions such as how the transformations of production and employment happen during the economic development process, what characterises each stage of the transformation and what changes are indicative in the transformations. In China, there is little agreement on the way these transformations take place from either a theoretical or an empirical perspective, for the following reasons.

First, the explanations and predictions of development economics vary. For example, while Lewis (1954, 1958) considered rural-to-urban migration an integral part of dual economy development in developing countries, he in fact assumed that this process was a one-way movement, whereas Todaro (1969) and Harris and Todaro (1970) viewed it as a circular movement following a repetitive ‘come-and-go’ pattern.

Second, there have been dissimilarities with respect to the pattern of these transformations among countries and across time, which have made it difficult to determine any stylised facts about the two types of transformations. While Japan, Korea and some other countries accomplished their modernisation through massive rural-to-urban migration decades ago, many developing countries—especially in Latin America and East Asia—have been trapped by ‘urban diseases’ such as extreme poverty and slums in urban areas.

Third, the changes in China have been too fast for scholars and practitioners to keep pace with. Conventional wisdom—such as the notion of a longstanding and everlasting excessive labour force in rural areas—prevents observers from understanding the potential for changing situations in labour demand and supply. This is particularly relevant in China’s case.

The reality and dynamics of China’s rural labour shift, and of its turning point in particular, can be observed through the theoretical framework of Lewisian development economics. Equally important is to apply the theory of demographic transition to China to understand the changes in demographic structure that have happened in the past decade. Due to the implementation of strict population control policy and social and economic developments in China in the past three decades, in combination with reform and opening up, rapid economic growth has been underpinned by a rapid demographic transition from high to low fertility, and the consequent increase in the labour force as a proportion of the population. Econometric analysis shows that the declining dependence ratio has accounted for 26.8 per cent of per capita gross domestic product (GDP) growth during the period 1982–2000 (Cai and Wang 2005).

However, in recent years the main source of growth of the urban working-age population has been in-migration of the rural labour force, and it is predicted that by about 2015, the out-migrating working-age population in rural areas will not be able to meet the demand for the working-age population in urban areas. That is, the total working-age population of the country as a whole will stop growing by this time and begin to shrink afterwards. The dependence ratio of the population will then begin increasing dramatically and the conventionally recognised demographic dividend is expected to vanish. The tension between this population structural change and strong economic growth has been reflected in the recent phenomena of rising wages and a shortage of unskilled migrant workers.

Setting the Lewis turning point as a milestone of development, a theoretical and empirical recognition of the end of an unlimited labour supply in China can help to identify the potential areas in which efforts can be made to sustain economic growth and harmonise the society in the near future. Migrant workers undoubtedly are at the centre of the theoretical cognition and the policy focus.[1] In a sense, changes in the status of migrant workers will determine the future vision of economic growth and social stability in China. In the 20 years to 2030, the consequences of China’s demographic transition will be further revealed, as the working-age population stops growing in 2015 and the total population reaches its peak in 2030. For a country such as China, which has realised its rapid economic growth through fully utilising an abundant and cheap labour force, the challenges brought about by the demographic transition have to be tackled so the country can exploit the potential of the demographic dividend in the short and medium run and transform its growth pattern in the long run.

This chapter is organised as follows. The next section explains the implications of the Lewis turning point for the labour supply and hence for economic growth. Investigating the trends of rural-to-urban migration and more general labour market changes shows that agriculture no longer serves as a pool of surplus labour; rather rural workers’ migration to and settlement in urban areas has become irreversible and inevitable. The next section discusses the outdated policy implications of the Todaro paradox in the circumstances of the Lewis turning point. This suggests that there is no reason to expect a come-and-go pattern of rural labour migration and that the appropriate policy choice is to push forward with urbanisation by transforming migrant workers into urban residents. The subsequent section shows the urgency and feasibility of including migrant workers in the urban social security system from the viewpoint of government policy orientation. The chapter concludes with some policy suggestions.

The irreversibility of rural–urban migration

There has been much disagreement about whether (or when) China has reached (or will reach) its Lewis turning point (Garnaut and Huang 2006; Cai 2008a, 2008b; Garnaut 2010). This is not all that surprising when, according to Lewis (1972) and other authors (for example, Ranis and Fei 1961), there are in fact two turning points as a consequence of development in a dual economy. The period when the growth of labour demand exceeds the growth of labour supply—and hence the wage rate of unskilled workers begins to rise—is the first Lewis turning point. At this point, the agricultural wage is not yet determined by the marginal productivity of labour, so a productivity differential between the agricultural and modern sectors still exists. Subsequently, the point at which wages in the agricultural and modern sectors are determined by their respective marginal productivities of labour and are equal to each other is the second Lewis turning point, which is referred to also as the commercial point. When an economy reaches the latter point, it is no longer a dual economy. This chapter intends to discuss the first of these two turning points.

The Lewis turning point is not, and should not be, a black-and-white watershed distinguishing between two stages of development, but is rather a transitional period bridging them—or it can be viewed as the starting point of a new historical trend in the course of economic development (Minami 1968). In this regard, while 2004 was a significant year signalling the turning point, the longer period around it is the focus of this study. In what follows, we examine the different characteristics of the labour market before and after the turning point.

During the stage long before the Lewis turning point, since there was a large reservoir of surplus labour in agriculture and the marginal productivity of labour in that sector was very low, the shift of workers from agricultural to non-agricultural sectors did not impact on agricultural production—that is, labour migration at this stage did not cause a significant change in the production mode in agriculture. On the other hand, because non-agricultural sectors during this stage absorbed the transferred labour force only marginally and sporadically, and the urban authorities frequently dispelled migrant workers when urban labour markets came under pressure (Cai et al. 2001), the agricultural sector still served as a pool of surplus labour. With the arrival of the Lewis turning point, however, circumstances have shown some fundamental changes, which we explain as follows.

First, the methods of agricultural production have changed in response to the massive and unremitting outflow of workers. Such outflow, given its large scale and steady growth, has accelerated agricultural mechanisation and modernisation and has pushed a transformation of agricultural technological change from being of the labour-use type to the labour-saving type. Examining the changes in agricultural mechanisation clearly shows this trend. During the first three decades of economic reform, the total power of agricultural machinery has strengthened, and even with the enlarged base the growth has shown no sign of decline in recent years.What is more notable is the changed composition of different sized agricultural tractors and tractor-towing machinery. In the period 1978–98, when there was surplus labour in agriculture, the annual growth in the capacity of large and medium-sized tractors was 2 per cent annually, while that of small-sized tractors was 11.3 per cent. In the period 1998–2008, as the mass labour force shifted from agricultural to non-agricultural sectors and, as a result, there emerged stronger demand for labour-saving technological changes, the capacity of large and medium-sized tractors increased by 12.2 per cent annually and that of small-sized tractors decreased by 5.2 per cent. Changes in the growth rates of different sizes of tractor-towing machinery show a similar trend, with the annual growth rate of large and medium-sized tractor-towing machinery increasing from zero per cent in the period 1978–98 to 13.7 per cent in 1998–2008, whereas the annual growth rate of small tractor-towing machinery declined from 12.1 per cent to 6.9 per cent in the same period.

As a result of falling labour inputs and rising physical capital inputs in production, Chinese agriculture’s capital–labour ratio—which is denoted by the ratio of physical inputs to labour inputs—has risen rapidly since 2004 (Figure 15.1). According to the theory of induced technological changes (Hayami and Ruttan 1980), this labour-saving tendency during the rapid process of agricultural mechanisation is the natural result of the ultimate abatement of the surplus labour force in agriculture. It is hardly surprising that the total factor productivity (TFP) of the agricultural sector has also witnessed a rapid rise during the same period—increasing by 38 per cent between 1995 and 2008, with a sudden rise after 2004 (Zhao 2010).

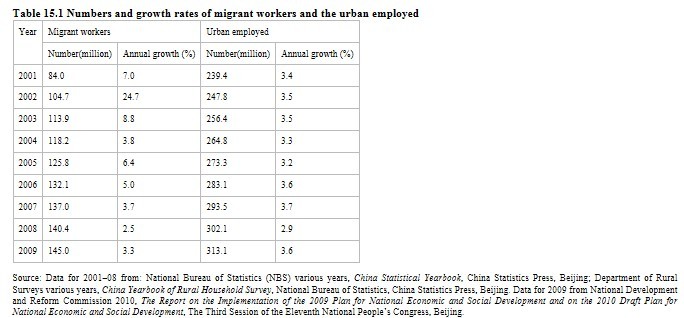

Second, urban demand for migrant workers has become increasingly rigid. As the result of demographic transition, during which process the urban age structure changes faster than the rural age structure, economic growth in urban sectors depends heavily on labour supply through migration. And yet, as shown in Table 15.1, while the total number of migrant workers from rural to urban areas for six months or longer continued to grow from 78.5 million in 2000 to 145 million in 2009, the growth rate decreased over time. In the meantime, the employment of urban locals continued to increase, and its growth rate remained constant. In 2009, nearly one-third of urban employees were rural migrants and they were dominant in some sectors such as construction. At the same time, migrant workers tend to reside and work in cities secularly (Zhang et al. 2009). In any event, urban sectors can no longer afford a retreat of such a large proportion of the labour force.

According to a survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) in early 2009, at the end of 2008 rural workers working in non-agricultural sectors for more than six months totalled 225 million, of which 140 million were migrant workers across townships, accounting for 62.3 per cent of total farmers-turned-workers, and 85 million, or 37.7 per cent, worked in non-agricultural sectors within home townships. Among migrant workers, 112 million still had family members in home villages, accounting for 79.6 per cent of all migrants, while 28.6 million migrated from home villages with their entire families, accounting for 20.4 per cent (Sheng 2009).

The two trends described above have altered the characteristics of labour migration after the Lewis turning point. In the period before the turning point, the cyclical changes of demand of the urban and non-agricultural sectors for labour often bring about a reverse rise and fall of the labour force engaged in agriculture. The amount of agricultural employment is not determined by the sector’s need per se but statistically is a residual term and thus agriculture still serves as a pool of surplus labour. After the turning point, however, fluctuations in the labour demand of urban and non-agricultural sectors no longer cause reverse changes in agricultural employment, because the urban and non-agricultural sectors gain the capacity to accommodate short-term labour market fluctuations. As a result, agriculture no longer provides a pool of surplus labour.

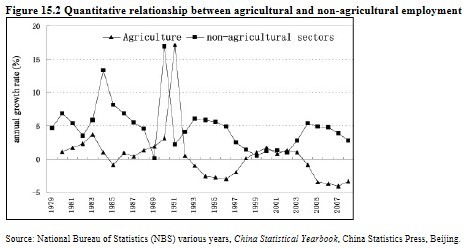

As shown in Figure 15.2, the correlation between growth rates of non-agricultural employment and of agricultural employment differs statistically before and after the turning-point years. In the period before the mid1990s, growth rates of non-agricultural and agricultural employment showed drastically fluctuating and positive growth rates, because the labour force continued to grow. While the rural surplus labour force faced the pressure of transfer and the constraints of non-agricultural employment opportunities, the two employment growth rates showed no stable correlation. After the mid1990s, while growth rates of non-agricultural and agricultural employment became more stable, they also became significantly and negatively correlated. During the period 1998–2008, the correlation coefficient between the growth rate of non-agricultural employment and the growth rate of one year lagged agricultural employment was –0.748, with declining agricultural employment in most years. The most significant change happened in 2004 when the high growth rate of non-agricultural employment and the negative growth rate of agricultural employment were highly correlated. In conclusion, while we consider the Lewis turning point to in fact be a transitional period, the year 2004 is still indicative of that period beginning.

The end of the ‘Todaro dogma’

Michael Todaro is widely known for his profound research on internal migration in developing countries. His most influential theory is the so-called ‘Todaro paradox’ (Todaro 1969; Harris and Todaro 1970). He argues that it is the differential of expected wages between the rural and urban sectors that encourages rural workers to migrate. Since the urban expected wage is adjusted by the urban unemployment rate, the paradox is this: efforts made by the government to reduce the unemployment rate will increase the difference of expected wages between rural and urban sectors and thus motivate more migration, which in turn can lead to more unemployment. A further implication is that any efforts made to improve the status of migrants working in urban areas can encourage more migration, thereby deteriorating the potential for migrants to find employment and residencein urban areas. Accordingly, the ‘Todaro paradox’ has been translated into a ‘Todaro dogma’, which views labour migration as a pattern of ‘comeand go’, rather than of permanent settlement, and thus the implementation of policies aiming to control and even restrict the process of rural-to-urban migration is regularly implied.[2]

The Todaro paradox rests on the assumption that there is no unemployment in the agricultural sector—namely, that agriculture is a pool for depositing the surplus labour force. Correspondingly, the Todaro dogma tends to mitigate the social risks potentially raised by labour migration, through balancing the push and pull forces between the rural and urban sectors, and especially through strengthening the role of rural areas in absorbing surplus workers. From the viewpoint of economic development, such an assumption is insufficient to conduct a dynamic analysis, because it fails to take into account the fact that the agricultural share of employment declines over time in the development of the dual economy.

As mentioned previously, the Chinese economy is already inthe stage of development expressed by the Lewis turning point, which suggests that the Todaro paradox might no longer hold. Thus there is a need to revise the policy orientation implied by the Todaro dogma. Before the Lewis turning point arrived, during each period when urban sectors suffered a cyclical downturn, migrant workers frequently returned to their rural homes and their contracted land provided them with shelter and some employment support. That mechanism prevented floating workers from becoming unemployed and hence falling into absolute poverty. Given the lack of social protection for migrant workers, this has indeed served as a buffer against economic and social risks. Once agriculture does not serve as a pool of surplus labour, however, and labour migration no longer follows a come-and-go pattern, this mechanism for risk alleviation no longer exists.

The employment adjustment of Chinese migrant workers in the face of the global financial crisis resonates with international experience. After a short break during the Chinese New Year period in early 2009, migrant workers immediately returned back to their urban jobs, and through relocation from manufacturing to service and construction sectors, they achieved comparatively full employment—so much so that a migrant worker shortage occurred shortly afterwards. This evidently suggests that the management mode of labour migration based on the Todaro dogma and the conventional wisdom of a come-and-go pattern no longer characterise the new stage of development.

In contrast with the period before the Lewis turning point, when urban governments regularly drummed out migrant workers each time their cities had employment pressure (Cai et al. 2001), during the years 2008–09, as countermeasures to cope with the negative impacts of the financial crisis on employment, urban administrators relaxed the restriction on ambulatory pitchmen, which helped migrant workers shift their jobs to the informal service sector in the first place. Then, as the government-led stimulus plan was implemented, and since the structure of investment had become more biased towards infrastructure and services, more and diversified job opportunities were created (Cai et al. 2010).

This is very similar to Japan’s experience in that, after the arrival of its Lewis turning point, the massive outflow of rural workers who settled and found jobs in urban areas in the 1960s has never been reversed, despite upsurges and recessions in the urban economy since then. During urban economic downturns in the country, workers originating from rural areas have not returned to agricultural production. Instead, in coping with each of the economic crises, their employment has been adjusted from the manufacturing to the service sector and has become more diversified. As a result, those workers have settled to become urban residents.

On the other hand, Chinese migrant workers’ willingness and tendency to live and work permanently in urban areas can conflict with the reality that they lack legitimate urban residential identities. When urban enterprises encounter difficulties, migrant workers are the first group of employees to be affected. Therefore, while being vulnerable in job and wage security and inadequately covered by social safety nets, they also suffer the worst labour relations. According to a survey conducted in 2009 (Ru et al. 2009:7–8), labour dispute cases accepted and heardby courts had increased by 30 per cent in the country as a whole and by 40 to 150 per cent in coastal provinces. Migrant workers became the dominant accusers in those cases, ranging from wage arrears to social security entitlements. This indicates the existence of social risks caused by employment and income insecurity, on the one hand, and the urgent need for revising the conventional mode of regulating the labour market, on the other. That is, in the new stage of development after reaching the Lewis turning point, urbanisation should be deepened through a strategy of transforming farmers-turned-workers into migrants-turned-residents.

The manifestation of the end of the Todaro dogma is rapid urbanisation, which is attributed overwhelmingly to migrant workers becoming secular residents in urban areas. Such a rapid urbanisation rate, however, is more statistical than material under the unique circumstance of China’s hukou (household registration) system. The difference between statistical and real urbanisation suggests that while farmers have turned to migrant workers and have counted as urban residents, they are not real citizens in urban areas.

In the planning period, when strict hukou control prevented spontaneous migration, the division of agricultural and non-agricultural hukou identities became a practical method to define who were counted as urban residents and who were counted as rural residents. For example, the second and third National Censuses, conducted in 1964 and 1982, respectively, both defined people with non-agricultural hukou as urban residents and people with agricultural hukou as rural residents.

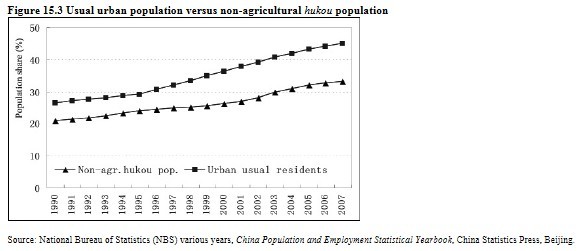

With rural-to-urban migration becoming more and more common through the reform period, and since hukou reforms have not kept pace with the expansion of migration, hukou identity no longer accurately reflects real residence in rural and urban areas. In response to this, the fourth National Census used the concept of ‘usual residence’ to distinguish between rural and urban residents by defining people who left their rural home village and lived in an urban area for more than one year as usual residents of that urban area. After the 1990 census, the National Bureau of Statistics adjusted all data between 1982 and 1990 based on the criterion of one-year residence. The fifth National Census shortened permanent residence to six months—that is, those rural migrants who lived in cities for more than six months were considered urban usual residents, regardless of their place of household registration. As a consequence, there appears to be a large difference between the proportion of the urban population and the proportion of the non-agricultural hukou population—a difference as large as 12 percentage points in 2007 (Figure 15.3).

Due to the fact that a large proportion of the statistically defined urban population is still engaged in agricultural activity, Chan (2009) claims that China’s urbanisation level is overestimated by 10 per cent. Although urbanisation involves a shift from agricultural to non-agricultural activities, it is more typically characterised by population concentration and industry agglomeration. Hence, the engagement of fractional urban residents in agriculture is not sufficient evidence to conclude that urbanisation is overestimated. Because the hukou system is a unique institutional arrangement of China’s and there are ample welfare implications behind it, it is more meaningful to understand Chinese-style urbanisation within the context of the hukou system and its public service content.

The fact that rural workers can now freely migrate to and work in cities signifies important progress in reforming the hukou system—to which the current level of urbanisation can be largely attributed. In this sense, the present urbanisation level should not be considered an overestimate. Accordingly, I do not agree with the arguments by Chan and Buckingham (2008) that suggest that the cumulative effect of the new round of hukou reform has nothing to do with the abolition of the hukou, but makes migration harder than before. One can hardly conclude that, given the widespread employment of migrant workers in urban sectors, the entitlements of free residence in urban areas and, as a result, the substantial expansion of migrant numbers in cities.

The significant increase in the share of the population with non-agricultural hukou, especially in recent years, is an indication of hukou reform progress. Compared with the period 1990–99, in which the annual growth rate of the non-agricultural population share was 2.3 per cent and that of the urban ‘usual’ population share was 3.1 per cent, in the period 1999–2007 the annual growth rate of the non-agricultural population share increased to 3.2 per cent and that of the urban ‘usual’ population share increased to 3.2 per cent. Both these growth rates were fast compared with the world average (Cai 2010). However, since there is still a difference between the two population groups—which is reflected in the gap of access to public services between farmers-turned-workers and migrants-turned-residents—there is great potential for further urbanisation through narrowing the difference between the ‘usual’ urban population and real urban residents.

This urbanisation pattern is an atypical one in terms of equal access to public services. Those migrant workers and their accompanying family members, though counted as usual urban residents, are not fully covered by social security and more widely by other forms of social protection. They do not enjoy equal entitlements to public services such as subsidised housing and children’s elementary education. This incomplete urbanisation has depressed the effect of urbanisation on economic growth and social development. More concretely, because migrant workers without urban residence identity still consider their rural home as their final destination, they behave like rural residents, who consume less and save more owing to comparatively low income and the lack of social protection. At the same time, urban construction does not take into account migrants’ demand for public infrastructure. Therefore, individual and public consumption, which would have become demand sources for spurring economic growth, especially in the service sector, have been held back.

Requisite conditions for equalising access to public services

One of the changes brought about by the Lewis turning point is manifested in the government’s policy orientation towards labour migration. The Chinese central government has been conceptualised as a typical developmental or entrepreneurial state (Oi 1999; Walder 1995), while Chinese local governments are seen as being competitive (Herrmann-Pillath and Feng 2004). It is well documented that under the decentralised fiscal system, local governments have had strong incentives to spur local economic development and have thus tried to ensure that government functions in an efficient way.

Local governments have various ways of trying to reach their development goals—from intervention in economic activities to the provision of public policies. Through a ‘vote with their feet’ model, Tiebout (1956) explained local governments’ behaviour of providing public services, trying to find a ‘market-type’ solution for public goods provision. This hypothesis implies that given particular potential migrants’ needs and preferences for public services, they choose their destinations based on information available to them on public services provided by local governments. Similarly, by deciding and adjusting how to provide public goods and create positive externalities, local governments try to attract or deter potential migrants in accordance with their own demand and preferences for the number and composition of local dwellers.

Although there has been extensive debate about the Tiebout model, this hypothesis does provide a powerful tool for our analysis of the incentive compatibility of local governments in making policies towards migrant workers, as they recognise the increasing importance of migrant workers to local economic development. In the development of a dual economy characterised by an unlimited supply of labour, any number of workers demanded can be met without a noticeable increase in the wage rate—namely, the labour force does not become a bottleneck limiting economic growth. Therefore, the main arena in which local governments—even of a developmental type—intervene in economic development is not in labour markets but in attracting physical capital inflows.

After the Chinese economy reached its Lewis turning point, and labour shortages had begun to occur regularly, while employers began competing for workers by increasing wages, improving work-related welfare and working conditions, local governments utilised various measures to create a better environment for local cities to attract workers. One notable practice is to include migrant workers under the umbrella of labour market institutions and social protection, which includes raising minimum wage standards and enhancing the coverage of social security and other public services.

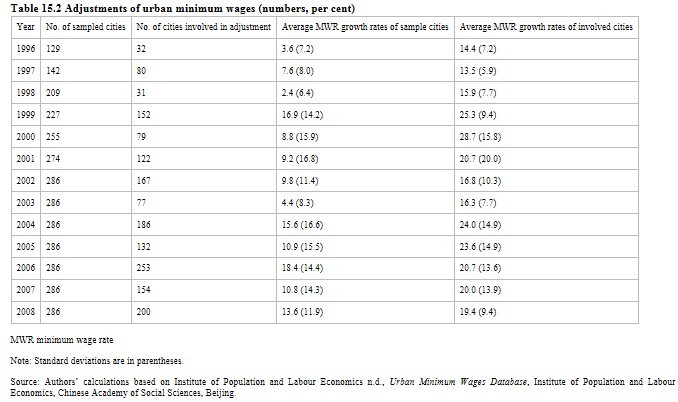

For example, adjusting the level of minimum wages is a mechanism that has been used frequently in recent years by local governments to intervene in wage setting. The minimum wages scheme has been put into practice since The Regulation on Minimum Wages in Enterprises was issued in 1993 and the Labour Law in 1994. The Labour Law authorised local governments to decide their standards in accordance with locallydifferentiated standards of living. Early on in its implementation, minimum wage levels were low and rarely enhanced, and the scheme was rarely applied to migrant workers. The levels of minimum wages and the frequency of their adjustment slowly increased, however, in the late 1990s, and further noticeable changes have occurred in the new century. Since the migrant labour shortage became widespread in 2004, the central government has called for a frequency ofadjustment of minimum wages of no more than two years. At the same time, local governments, pressured by local labour shortages, have leapfrogged to increase minimum wages (Table 15.2), which are now applied to migrant workers also. In the same period, minimum wages have been adjusted in an attempt to keep pace with the increase in market wages.[3]

Migrant workers are, however, still left behind when it comes to social security coverage, particularly pension and unemployment insurance. According to the Employment Contract Law issued in 2008 and other regulations, migrant workers are entitled to be included in urban basic social security. The participation rate of migrant workers in social security programs is, however, rather low. A survey conducted by the NBS in 2009 shows that only 9.8 per cent of migrant workers living in cities for more than six months participated in basic pension programs and 3.7 per cent in unemployment insurance programs (Sheng 2009). Since there is no legal handicap for migrant workers to participate in various social security programs, the willingness of workers and employers to join rests largely on each scheme’s design. Before conceptions of scheme design can be decisively altered, local governments can find some alternatives if they are willing to expand the coverage of public services in order to attract more labour, and that can also bring forth social security reform for the central government. It is therefore important to consider the interaction between the right conditions for equalising migrant workers’ rights to public services created by the arrival of the Lewis turning point and the practices of the central and local governments in related arenas.

The general concerns about including migrant workers in the urban social security system have been threefold. First, authorities have long been concerned with the burden of migrants’ participation on the affordability of social security funds. Second, as for the migrant workers’ and employers’ incentives to participate in the programs, the fact that not all social security schemes are portable and transferable across regions has deterred migrant workers and their employers from participating, since migrant workers’ employment is not stable. Third, the high contribution rates required have reduced affordability and hence the incentives for employers to participate in the programs.

Turning to pensions, the conditions for an inclusive basic pension system have mellowed. The current basic pension system for urban enterprises has two parts: social pooling and individual accounts. The system was formed in 1997 and it has long mixed up the pooling and individual accounts, because the inadequacy of social pooling was required to be compensated by individual account collection. That caused a problem of empty individual accounts, and the system is indeed a pay-as-you-go type with only a nominal fullyfunded component. The problem of inadequacy of the social pooling accounts is twofold. First, a huge historic debt was accumulated during the pre-reform period, during which there was no accumulation for workers’ pension funds, since the State guaranteed retirement support for all state-owned enterprises’ employees, who overwhelmingly dominated urban employment. Second, the dependence ratio has increased since the initiation of reform and is expected to grow over time, according to demographic predictions made by the United Nations (UN 2009).

There have, however, been some significant changes in the system in recent years. First, many of the ‘middlemen’ (those who had not yet retired in 1997) retired and were well supported by the social pooling pension, alongside with the ‘old men’ (those who retired before 1997). That is, a large portion of historical debt is disappearing as time passes. Second, as the pilot program for basic pension system reform aimed at substantiating individual accounts in Liaoning Province has been completed and extended to 11 more provinces, individual accounts have accumulated, which is reflected in the current positive balance of more the RMB700 billionin the revenues and expenditures of the basic pension fund. Third, migrant workers whose ages are concentrated between twenty and thirty have become widely engaged in urban activity, which significantly reduces the dependence ratio of the retired to working population—that is, migrant workers not only contribute to social pooling, they build a full individual account if they can be included. With all these changes reflecting positive improvements in the basic urban pension system, when a fuller inclusion of migrant workers in the system can be reached, the financial difficulties of the system will not be aggravated but substantially eased (Cai and Meng 2003).

The lack of portability has been the decisive constraint on migrant workers’ incentives to participate in the basic pension system. The basic pension fund was not built at the provincial level in 19 provinces and it was not even at the municipal level in some regions until 2007. The low levels of social pooling have restricted the portability of basic pensions and prevented highly mobile migrant workers from transferring their pension contributions. As a result, when a migrant worker changes his workplace, he has to surrender his pension contribution; and when labour market shocks happen, a mass of migrant workers retreats from the program. Given that only the individual accumulation but not the pooled contribution is refundable, neither the migrant workers nor their employers have much incentive to participate.

In order to tackle this problem, the central government has recently issued ‘Interim Measures on the Transfer of Continuation of Basic Pension for Urban Enterprises Employees’, which stipulates that all workers who participate in the basic pension program, when migrating across provincial boundaries, will be guaranteed a transfer of their individual and pooling accounts to their new workplace. This new regulation provides institutionallyguaranteed portability for migrant workers’ pension entitlements.

A small fraction of migrant workers has so far participated in the unemployment insurance program. While the Employment Contract Law came into effect in 2008—requiring employers to sign contracts with migrant workers so that the latter could be included in various social security programs—government departments holding on to the Todaro dogma and hence considering migrant workers a highly mobile group of workers have not had a strong incentive to enforce this regulation. That is, the authorities expect that such high mobility might cause circumstances in which migrant workers contribute less to and benefit more from the program. As discussed earlier, the Todaro dogma is preventing an accurate understanding of migrant workers’ real status in the labour market.

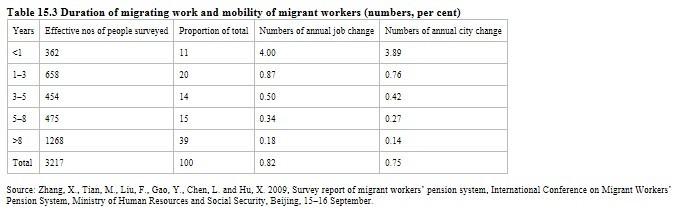

The current unemployment insurance program requires a minimum contribution period of one year and warrants a period before benefiting of one to two years. Migrant workers’ employment features are not incompatible with this regulation. According to a recent survey (Zhang et al. 2009), only those migrant workers who entered cities for less than one year, and account for 11 per cent of all samples, changed their jobs and cities within a year. All others who migrated out of rural areas for more than one year changed jobs and cities of employment less than once within a year. And the longer the migrants stayed in a city, the less frequently they changed their jobs or cities (Table 15.3). Furthermore, migrant workers usually accept low reservation wages and less satisfying jobs, so they take less time to find a new job once encountering unemployment. In conclusion, the labour market status of migrant workers can perfectly meet the requirements of the minimum time of contributing and the warranted time of benefiting.

Since 2003, the revenue of the unemployment insurance fund has significantly outweighed the expenditure of the fund, so the balance accumulated to RMB128.8 billion by 2008, which was five times the total expenditure of the same year. As a pay-as-you-go type fund, consecutive excesses of revenue over expenditure are not necessarily advisable, particularly when a huge surplus has been accumulated. It is such an overrun that causes an asymmetry between the contributions and benefits of potential participants and reduces the incentive to participate. Therefore, it is feasible to adjust the contribution rate of unemployment insurance in order to enhance incentives to participate and to expand the coverage of the program. This is an example of strengthening the levels of social protection for migrant workers.

In fact, as local governments have begun to recognise the need to increase social protection to increasingly scarce workers, local government authorities for labour and social security have tended to flexibly adjust the contribution rates of various social security programs, which the central government is legally required to adjust. While tackling the global financial crisis, the central government introduced a series of employment support policies, which allowed qualified enterprises to postpone their payments of social security contributions and reduce workers’ contributions to social security funds. Taking advantage of the temporary flexibility, local governments in some regions—especially those where labour shortages had been strongly felt before the financial crisis occurred—increased the social security coverage of migrant workers by debasing the contribution rates during the period.

Moreover, one can observe a host of phenomena that had rarely happened before the shortage of ordinary workers became widespread across the country. First, local governments in labour-migration destinations have tried to establish formal coordination mechanisms with their counterparts in labour-sending regions in order to help local enterprises secure a stable supply of labour. Second, some municipal governments have relaxed certain criteria—such as the size of purchased housing, the length of employment contracts and accumulative years of contributing to social security programs—for migrants to obtain urban hukou. All these efforts have been made mainly by local governments and indicate incentive compatibility in people-centred urbanisation.

Conclusions

The combination of a rapid demographic transition from high to low fertility, an institutional transition from a planned to a market economy and a continuing transition from a dual society to an integrative one has contributed significantly to the ‘Chinese miracle’ that has received worldwide attention. Such a compressed process of socioeconomic development and institutional transition provides an interesting case for studies of development in a dual economy. The fact that China’s development of a dual economy is passing through the Lewis turning point has injected new life into the economic development theory coined by Arthur Lewis. The application of other relevant paradigms in development economics to the China case helps us to assess the stage of, and to identify challenges and opportunities facing, China’s socioeconomic development.

As a result of the arrival of the Lewis turning point, migrant workers have become an indispensable source of labour for urban sectors—in other words, non-agricultural sectors’ demand for migrant workers has become unvarying, or rigid. Since agriculture no longer provides a pool of surplus labour and labour migration no longer demonstrates a come-and-go pattern, there is a need for synchronisation between urbanisation and industrialisation. While China has urbanised at the world’s fastest pace in recent decades, this speed can be attributed to counting migrants as de facto urban residents, who live in cities for more than six months but have no formal access to public services due to their lack of local hukou.

Now that the existing exclusiveness of urban public services provision is rooted in the hukou system, the extension of those provisions to migrant workers should logically initiate from hukou system reform. Because many municipalities have little financial capability to cover all migrants with equal provision of public services—such as social security, migrant children’s compulsory education and entrance to higher education and subsidised housing—and while there has been some hukou reform in some cities, there has not been a significant breakthrough overall. The hukou system is, however, significant only because of its affiliation with various urban public services that favour residents with local hukou identity. Under the circumstance of labour shortage, and in pursuit of attracting and keeping migrant workers, developmental local governments will change their function to focus more on equal public services provision. When non-hukou migrant workers and their accompanying families can enjoy more equal rights to urban basic public services, the hukou per se becomes less meaningful. That is, real hukou reform can be embodied in the process of transforming farmers-turned-workers into migrants-turned-residents.

Compared with other developing and transitional countries, in China, the hukou system is unique. China’s development of a dual economy has therefore been characterised by the transformation of farmers to urban workers without entitlement to public services, particularly regarding access to social protection, which has driven rapid urbanisation with Chinese characteristics. As reaching the Lewis turning point brings about a labour shortage, a new round of urbanisation with Chinese characteristics will be shifting towards transforming migrant workers into entitled residents. Just as China’s development has already created the largest number of farmers-turned-migrant workers in human history, it can also be expected to create the largest number of migrants-turned-urban residents in the world in the next two decades.

References

Cai, F. 2008a, Approaching a triumphal span: how far is China towards its Lewisian turning point?, UNU-WIDER Research Paper, No.2008/09, United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research, Helsinki.

Cai, F. 2008b, Lewis Turning Point: A coming new stage of China’s economic development, Social Sciences Academic Press, Beijing.

Cai, F. 2010, ‘How migrant workers can contribute to urbanization: potentials of China’s growth in post-crisis era’, Chinese Journal of Population Science, no.1, pp.2–10.

Cai, F. and Meng, X. 2003, ‘Demographic transition, system reform, and sustainability of pension system in China’, Comparative Studies, vol.10.

Cai, F. and Wang, D. 2005, ‘China’s demographic transition: implications for growth’, in R. Garnaut and L. Song (eds), The China Boom and Its Discontents, Asia Pacific Press, Canberra.

Cai, F., Du, Y. and Wang, M. 2001, ‘What determines hukou system reform?

A case of Beijing’, Economic Research Journal, vol. 12.

Cai, F., Du, Y. and Wang, M. 2009, Migration and labour mobility in China, Human Development Research Paper, no.9, United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report Office, New York.

Cai, F., Wang, D. and Zhang, H. 2010, ‘Employment effectiveness of China’s economic stimulus package’, China & World Economy, vol.18, no.1,

pp.33–46.

Chan, K. W. 2009, Urbanization in China: what is the true urban population of China? Which is the largest city in China?, Unpublished memo.

Chan, K. W. and Buckingham, W. 2008, ‘Is China abolishing the Hukou system?’, The China Quarterly, vol. 195, pp. 582–606.

Department of Rural Surveys various years, China Yearbook of Rural Household Survey, National Bureau of Statistics, China Statistics Press, Beijing.

Garnaut, R. 2010, Chapter 2 in this volume.

Garnaut, R. and Huang, Y. 2006, ‘Continued rapid growth and the turning point in China’s development’, in R. Garnaut and L. Song (eds), The Turning Point in China’s Economic Development, Asia Pacific Press, Canberra.

Harris, J. and Todaro, M. 1970, ‘Migration, unemployment and development: a two sector analysis’, American Economic Review, no.40, pp.126–42.

Hayami, Y. and Ruttan, V. 1980, Agricultural Development: An international perspective, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London.

Herrmann-Pillath, C. and Feng, X. 2004, ‘Competitive governments, fiscal arrangements, and the provision of local public infrastructure in China: a theory-driven study of Gujiao municipality’, China Information, vol. 18,

no. 3, pp. 373–428.

Institute of Population and Labour Economics n.d., Urban Minimum Wages Database, Institute of Population and Labour Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing.

Lewis, A. 1954, ‘Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour’, The Manchester School, vol. 22, no.2, pp. 139–91.

Lewis, A. 1958, ‘Unlimited labour: further notes’, The Manchester School, vol.26, no.1, pp. 1–32.

Lewis, A. 1972, ‘Reflections on unlimited labour’, in L. Di Marco (ed.), International Economics and Development, Academic Press, New York,

pp. 75–96.

Minami, R. 1968, ‘The turning point in the Japanese economy’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol.82, no.3, pp.380–402.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) various years, China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook, China Statistics Press, Beijing.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) various years, China Statistical Yearbook, China Statistics Press, Beijing.

National Development and Reform Commission 2010, The Report on the Implementation of the 2009 Plan for National Economic and Social Development and on the 2010 Draft Plan for National Economic and Social Development, The Third Session of the Eleventh National People’s Congress, Beijing.

National Development and Reform Commission various years, Compilation of Farm Product Cost-Income Data of China, China Statistics Press, Beijing.

Oi, J. C. 1999, ‘Local state corporatism’, in J. C. Oi (ed.), Rural China Takes Off: Institutional foundations of economic reform, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Ranis, G. and Fei, J. C. H. 1961, ‘A theory of economic development’, The American Economic Review, vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 533–65.

Ru, X., Lu, X. and Li, P. 2009, Analysis and Prospects of China’s Social Situation, 2009, Social Sciences Academic Press, Beijing.

Sheng, L. 2009, New challenges migrants are faced with on employment during the financial crisis, Paper presented to Urban–Rural Social Welfare Integration Conference, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, 16 April.

Tiebout, C. M. 1956, ‘A pure theory of local expenditures’, The Journal of Political Economy, vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 416–24.

Todaro, M. P. 1969, ‘A model of labour migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries’, American Economic Review, vol.59, no.1,

pp.138–48.

Todaro, M. P. 1985, Economic Development in the Third World, Longman, New York and London.

United Nations (UN) 2009, The World Population Prospects: The 2008 revision, United Nations, New York. <http://esa.un.org/unpp/>

Walder, A. 1995, ‘Local governments as industrial firms: an organizational analysis of China’s transitional economy’, American Journal of Sociology, vol.101, no.2, pp.263–301.

Zhang, X., Tian, M., Liu, F., Gao, Y., Chen, L. and Hu, X. 2009, Survey report of migrant workers’ pension system, International Conference on Migrant Workers’ Pension System, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, Beijing, 15–16 September.

Zhao, W. 2010, Analysis on potentials of China’s agricultural growth after Lewis turning point, Unpublished working paper.

[1] This is true not only for China but for the world, as is implied by the fact that Chinese workers were chosen as ‘People of the Year 2009’ by Time magazine.

[2] For an explanation of the Todaro dogma and the policy implications of the Todaro paradox, see Todaro (1985:Ch. 9).

[3] Cai et al. (2009) depict in detail the trends of increases in migrant workers’ wages, which we take as representative of market-determined wage rates of unskilled workers.

文章出处:China:The Next Twenty Years of Reform and Development,pp.319-340