Abstract: By clarifying officially published statistics on labor market and employment and combining them with micro survey data, this paper tries to depict the employmentgrowth and structuralchanges in rural and urban China and to break the myths believed by domestic and international scholars such as “zero growth of employment” and “unchangeable rural surplus labor pool”. The paper provides exact statistics about China’s labor market that previous studies fail to do, explaining how labor market develops, employment in both rural and urban areas increases and its structure diversifies, urban unemployment alleviates and number of rural surplus laborers reduces, as a result of economic growth, reform and opening-up. By examining demographic transition process in China, the paper also predicts the emerging trend of labor shortage, suggests a coming Lewisian turning point and reveals its policy implications to China’s sustainable growth.

Keywords: Labor market development; Employment growth; Surplus labor force; Lewisian turning point

1. Introduction

One of the consequences of China’s reform, development, and opening-up is its employment growth and structural changes. Exploring how that has happened, thus, is important for understanding the transition experiences of the past three decades. On the other hand, employment-related issues can only be correctly understood in the context of the reform, development and opening-up that characterize the Chinese type development of dual economy in the same period. Firstly, the Chinese experience corroborates the Lewis model of dual economy development in terms of how economic growth and structural changes can create job opportunities and revise the characteristic of an unlimited supply of labor. Secondly, the Chinese style development of dual economy has been accompanied by the transition from a planned economy to a market economy containing a labor force allocation mechanism. With both employment increases and a labor market shock during the course of economic reform, employment increase patterns change dramatically. Thirdly, under the background of economic globalization, the development of a dual economy and institutional transition have been accompanied by opening-up.

It is widely acknowledged that reform of statistical systems in China have lagged behind economic reform (for example Ravallion and Chen, 1999). The current statistical system is, however, consistent with the transition features of the Chinese economy described above. In fact, to those who are unable to capture the transition feature of China’s statistical system and thus do not know how to handle the statistical data in the perspective of economic transition and its logic that characterizes the Chinese reform and development, the statistics on employment seem to be insufficient in getting a complete picture in the arena, inconsistent among different categories of statistic, and separated from one source to another.

Lacking a thorough appreciation of such a statistical resource prevents scholars and policy makers from soundly understanding labor market developments in China. Instead, there are prevailing perceptions about the employment situation, which lead to inappropriate academic conclusions and thus irrelevant policy implications.

The incomplete knowledge about China’s labor market developments is twofold. First of all, understanding China’s achievements in reform, growth and participation in global economy is not in a consistent way. Second, examining employment is based on traditional statistical sources but not on changed situation. For example, if one still examines the employment changes by looking at traditional absorbers – state owned sector, collective sector and formal sector, he or she may conclude that China has experienced zero growth of employment since the late 1990s (Rawski, 2001), or, from another angle, the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) reform aiming at “breaking up the iron-rice-bowl” is responsible for massive lay-off and unemployment and decline in urban employment (Solinger, 2001a). Based on those verdicts, a host of literature has been published to emphasize difficulties of being employed for urban laborers and obstacles of mobility for rural laborers, but little has been revealed about the progress in labor market development (for example Solinger, 1999), and the ideas about endless rural surplus labor force and urban overstaffed workers persist, regardless of the overall changes in the economy as a whole. By unfolding and interpreting the official statistics with supplementary sources, this paper tries to draw an overall picture of the Chinese labor market and its direction, pinpointing where the economic development of China stands and implications for policy decisions.

The Chinese reform, without a clear blueprint from the beginning, was initiated and carried out to solve urgent problems in the economic system and to seek instant welfare gain. Although the 14th National Congress of the Communist Party of China clearly defined the objective of the economic reform as the establishment of a socialist market economy, the gradual approach of “crossing the river by feeling the stones” still characterizes the reform progress. For most of reform tasks, there are no fixed timetables and predetermined sequencing. With a superficial observation of this gradualism, scholars claim that reforms in some fields lag behind others. For instance, reforms of production factors markets, especially of labor market and capital market, have been considered as a backward arena relative to, for example, reform of commodity market (Lardy, 1994, pp. 8–14). One question arises from this conclusion: if reforms in such important fields as factors markets are really lagging behind the others, and therefore there is intrinsic incompatibility among different components of the entire economic system, how has the overall reform gained the far-reaching welfare effects of very rapid economic growth, enhanced productivity and improved living standards?

Given that the Chinese economic system is endogenously formed, with a high degree of intrinsic unity, inseparability among different components, and adaptability of each component to the whole system, the reform process is not arbitrary, but it is intrinsically logical (Lin et al., 2003). Meanwhile, while the reform, by and large, advances in a gradual and incremental manner, it also takes relatively radical measures in certain areas and at certain stages from time to time. The choices of forms and measures in the reform process depend on adaptability of different components of the economic system and on how much the society is capable of adapting itself to the reform.

The reform of employment policy, namely labor market development, has been such a series of events that are moderate and gradual most of time and sometimes when necessary are radical. Taking the employment reform as a whole and viewing it in a longer perspective, labor market development, namely growth and structural changes of employment and changes in ways of labor allocation, is not really in a backward position relative to the general process of reform. The employment system during the planned period consisted of three key components.1

First is the exclusive policy of overall urban employment. The pursuit of capital-intensive industrialization in a capital-scarce economy had limited employment absorption capacity in the urban sector. An absence of government intervention in allocating labor force was thought to lead to a high unemployment rate in urban areas and to endanger political stability. To secure stable and life-long employment for urban workers, government departments of labor and personnel put job distribution on the agenda in accordance with the overall economic planning. The only two absorbers of labor force were state-owned and urban collective sectors at the time. Once a worker was assigned to a post, he could neither have a chance to turnover nor have fear of dismissal and unemployment.

Second is the household registration (hukou) system, which separates population and labor between rural and urban areas and prevents integrated labor market from functioning. Since labor mobility was strictly restricted between rural and urban areas and across regions, many fewer rural surplus laborers than expected by Development Economics were absorbed by a heavy industry-oriented economic growth.

Third is a host of welfare policies, including rationing policy of basic necessities, urban exclusive social security policy and other public service provision policies, which, in addition to hukou system, effectively deterred labor mobility and equal treatment of residents between rural and urban areas. While serving to pursue the heavy industry-oriented strategy, all these institutional arrangements were implemented by sacrificing resources allocative efficiency, a depression of work incentives, and the formation of a large income gap between rural and urban areas (Yang and Cai, 2003).

China’s economic reform was pioneered by introducing household responsibility system into rural areas in the late 1970s. By contracting the former collective-owned farm land to individual households and making them the residual claimants of their marginal effort, the reform had the enormous effect of improving incentives in the agricultural sector and releasing the farm labor force from being solely engaged in agriculture work, producing an explicit labor surplus in rural areas. As a result, the rural labor force began its reallocation through three steps – that is, rural laborers first shifted from farming to other, diversified agricultural sectors, such as forestry, husbandry, and fishery, then transferred from agriculture to non-agricultural sectors, noticeably township and village enterprises (TVEs), and thirdly, migrated from rural areas to urban areas.

The gradual abolition of institutions deterring interregional migration typically under the planning system has been the key for increased labor mobility since 1980s. The practice has been carried out by central and local governments to remove restrictive regulations mainly in two areas. First, reforms of urban employment and welfare policies have improved the institutional environment under which rural laborers migrate to and work in urban sectors. All reforms such as expansion of non-public sectors, abolition of rationing, commercialization of housing, liberalization of employment regulation, and, to a lesser extent, reestablishment and reforms of social security have reduced costs for migrants’ living and working in cities by providing access to public services. Secondly, hukou system reform has moved forward in the direction of free migration since the overall reform began in the late 1970s and has accelerated since the new century. Despite the progress of hukou reform is uneven among regions, due to the intervention of and role played by policy, migrant workers’ working and living conditions significantly improved.

The reform in urban China is characterized by the government’s granting SOEs an increasing degree of autonomy and a partial claim to newly generated profit, on the one hand, and by the expansion of non-public-owned enterprises and their creating competitive environment, on the other. The demand for labor forces in newly developed sectors has been met by both rural migrant workers and turned-over workers from SOEs and collectively owned enterprises in urban area. The competition for managerial and technical staff and skilled workers in the non-public-owned sector and its superior efficiency brought about pressure on SOEs, creating a motivation for reforming the planning system of employment. While SOEs gradually gained autonomy in recruiting and hiring employees, the reform program termed “activating the system of permanent employment” initiated in 1987 touched upon the core system of the “iron rice bowl” and began revising the legacy of traditional labor policies under the planning system.

However, since there still existed soft-budget constraints on SOEs – namely, the government still imposes policy burdens on SOEs and thus tolerates their ill performance, on the one hand, and the non-public sector was not developed enough to absorb potentially dismissed workers by SOEs, on the other, their managers had insufficient motivation to utilize labor market as a distributor of resources. Only since the late 1990s when SOEs began to face a severe situation of lay-offs and unemployment has the relaxed state regulations of labor allocation and the autonomy of employment become stimuli for market development. When the negative impact of the East Asian financial crisis appeared in China in the late 1990s, the Chinese economy was experiencing the downturn of macro economy and rapid industrial structural change, many SOEs were unable to fully utilize their production capacity. As a response to this difficult situation, SOEs managers were forced to exercise their autonomy of disposing workers and thus a 100,000 urban workers left their posts. Since then, the employment expansion, including reemployment of the laid-off and unemployed, has mainly relied on the development of non-public sector and marketization of labor allocation.

In predicting the fate of China’s reform and development, many observers considered its overpopulation and resulting pressure of employment as the biggest challenge. Indeed, in the overall course of reform and opening-up, the Chinese economic growth has been characterized by development of dual economy. In the entire period of reform since the late 1970s, both the number and proportion of working-age population have been constantly increasing, with dependency ratio of the population declining correspondingly. This structural feature of population has guaranteed adequate supply of labor and helped obtain high savings rate in the course of economic growth. Thanks to the reform of resources allocation mechanism, which has gradually reduced labor market segregation, removed institutional obstacles deterring employment expansion and labor mobility, this potential demographic dividend resulted in by favorable population structure has been translated into comparative advantage of the Chinese economy in the process of China integrating into economic globalization and therefore deferred the phenomenon of diminishing returns to capital by fuelling the economic growth with extra source (Cai and Wang, 2005).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. After this introduction section provides background on the expansion and structural changes in employment and labor market transition and development in transitional China, Section 2 depicts the labor force mobility and reallocation among regions and sectors and estimates the present amount and proportion of surplus labor in rural area. Section 3 elaborates on how the increase and structural changes in urban employment happened, providing basic indicators reflecting labor market developments. Section 4 predicts possible changes in labor demand and supply. Section 5 concludes, and discusses these policy implications.

2. Transfer of rural surplus labor force

In 1978, before the reform began, the total share of rural employed persons was as high as 76.3 percent, a typical structure of agricultural economy. As the result of economic reforms, this share declined to 64.0 percent in 2005. This 12.3 percentage point change, however, does not seem match the achievements of speedy growth, enormous structural change and rapid urbanization over the past quarter century. Due to the existing hukou system, the statistics about rural employed persons presented here are not based on where they actually live but based on where they register as residents. In order to draw a more exact and thorough picture of rural labor force transfers, we need to take advantage of various sources of data beyond that statistical bound, because the expansion and full use of rural labor force have been accomplished through labor transfers from agriculture to rural non-agricultural sectors and from rural to urban sectors.

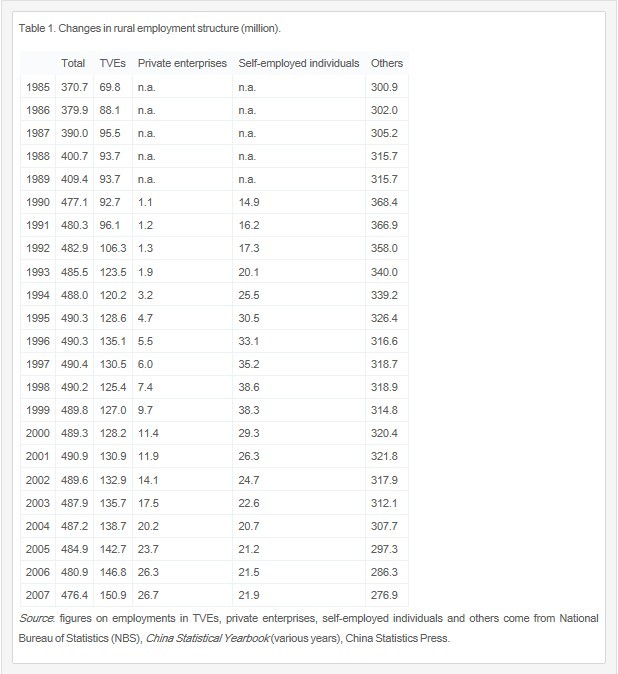

The widespread introduction of the household responsibility system improved incentives and made surplus labor in agriculture explicit. Meanwhile, the sectoral adjustment of rural economy created opportunities for laborers formerly engaged in agriculture to shift to non-agricultural sectors within rural areas. In Table 1, we show the changes in total number of rural employed persons and their distribution among sectors. During the period 1990–2007, employment in township and village enterprises (TVE) increased by 62.9 percent. Employment in private enterprises was only 1.1 million in 1990 and it increased to 26.7 million in 2007. Self-employed individuals increased by 46.7 percent and employment in others decreased by 24.8 percent. Until the mid 1990s, TVE was the dominant absorber of non-agricultural employment in rural areas by creating most incremental opportunities of employment, whereas private and individual enterprises played an increasingly important role in creating new rural jobs after the mid 1990s.

Since 19902, the category “others”, which theoretically consists of all agricultural, migrated and surplus laborers, has always been in decline. In practice, apart from labor shifts among rural sectors, there has been a host of factors reducing the amount of rural surplus laborers. First, agricultural productivity improves over time in a pace greater than in most of other industries ( [Hu and McAleer, 2002] and [Cai and Wang, 2008]). Statistically, the amount of laborers in agriculture tends to decline as machinery used in the sector increases. Given the declining trend of this whole category and an increase in migrants, we can infer an enormous reduction in the rural surplus labor force. Secondly, permanent rural-to-urban migrant workers defined as those who leave rural home to seek job in urban sectors for more than 6 months, increased from 80 million in 2001 to 150 million in 2009 (Table 2). Finally, as a result of demographic transition spurred by both socio-economic developments and nation-wide implementation of family planning policy, the rural fertility rate has substantially dropped in the past two decades, which in turn reduce the growth rate of rural working-age population. Adjusted by permanent migration, the usual rural working-age population has been declining in absolute term. By knocking off those who are not economically active – e.g. students at senior high school, labor force left to agricultural sector is a diminishing number.

All the experiences presented above contradict the conventional wisdom that suggests there are still mass surplus laborers in rural areas. Although about 30–40 percent of the agricultural workforce – in absolute terms is about 100 million to 150 million – was estimated as surplus in mid 1980s, according to then prevailing estimates (Taylor, 1993, Chapter 8), and 172 million surplus laborers were estimated, making up 31.5 percent of total rural labor, for 1990 (Carter et al., 1996)3, tremendous changes have happened since 1990, which cannot support the proposition that there are existing large reservoir and proportion of surplus labor force (Cai and Wang, 2008).

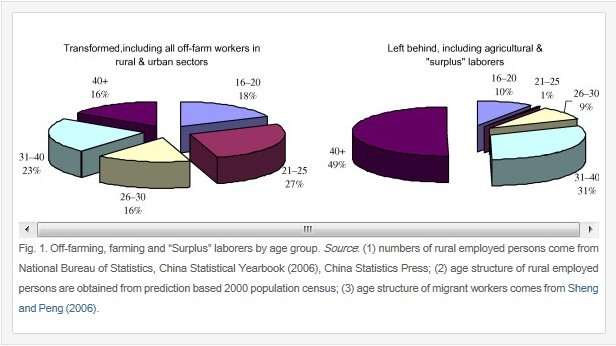

Even we assume that there are still surplus laborers left in rural areas, we can find that they are concentrated in older age, which make them the disadvantageous groups of rural population to migrate. Based on demographic exploration, we categorize two labor market statuses – transformed off-farm workers in both rural and urban sectors and left behind in either agricultural sector or “surplus” category – into five age groups: 16–20, 21–25, 26–30, 31–40, and over 40, respectively (Fig. 1).

According to population predictions based on the national census in 2000, we use the age distribution of the rural working-age population to proxy the labor force age structure. From the survey analysis by Sheng and Peng (2006), we also know the age structure of migrant workers. Based on rural laborers’ job preferences revealed by previous studies (Zhao, 1999), it is safe to rank rural laborers’ choices regarding willingness to take a job using the following ordering: rural non-agricultural job as first choice, migrant job as second, agricultural work as third, and being surplus labor if above alternatives are not available. Supposing that the age distribution of rural non-agricultural employees follows that of migrant laborers, we can acquire the age structure of all the transformed labor force. Then we calculate the difference between age distribution of the total labor force and that of the transformed labor force and obtain an age distribution of those laborers engaged in agriculture and those remaining in surplus, if we assume that the age structures of the two groups of laborers are similarly distributed, it is can be found that 50 percent of rural surplus laborers are older than 40 – that is, the absolute number of rural surplus labor aged between 16 and 40, which is the population group with active willingness to migrate, is minor, if there are indeed any.

3. Urban labor market: how has employment been created?

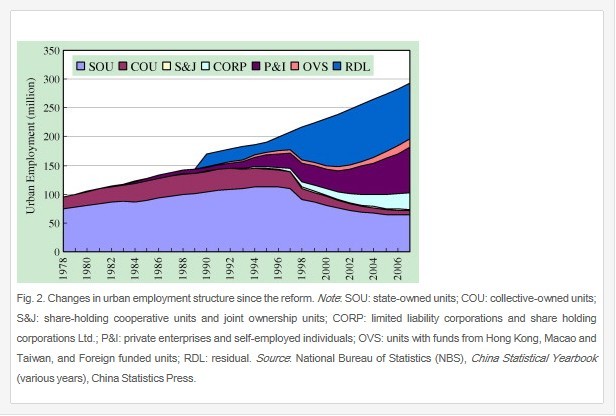

Since the reforms initiated in the late 1970s, strong economic growth has spurred a rapid increase in urban employment, and the trend has not diminished even after the labor market experienced severe shock. However, after the SOE’s employment reform aimed to improve efficiency by reducing the overstaffing in the late 1990s, the employment structure and the contributing components to employment expansion have changed dramatically (Fig. 2). Urban employment increased by 3–5 million per annum in the period of 1978 to the first half of 1990s – namely before SOEs initiated their employment reform – and it increased by 9 million in 1996. From then on, even mass lay-offs and unemployment did not stop the substantial employment expansion as 8.6 million jobs on average were created in the period of 1996–2007. In the same period, while employment in SOEs and collectively owned enterprises declined by 6.5 million each year, other newly emerged sectors such as corporations, joint ventures, private enterprises, self-employed business, and others together created 8.4 million jobs each year.

The substantial increase of unit employment in such newly emerged sectors offset the decline in state and collective employments in some degree, however, the most important source of urban employment increase come from the residual between classified and total employments. This residual of employment represents 96.6 million urban employees in 2007, which is more than the sum of state and collective employment and accounts for 33 percent of urban total employment. Explaining why this residual employment emerges statistically and practically will help us better understand the attributes of the employment growth and the changes in employment structure under a more liberalized labor market.

Statistically, the residual represents a gap in employment figures between unit-based reporting system and household-based survey.4 There are two factors in the unit-based reporting system causing underreporting of employment. The first factor is that some units were never included in the numerical statement system, which causes the error of “missing units”, as a result of diversification and informalization of the economy. The second factor is that units had a motivation to deliberately underreport the numbers of employees, or even to omit reporting, in order to reduce their burdens because the employment number in a unit is related to some obligations such as paying premiums to social security programs. Via labor dispatching agencies, enterprises employ the reemployed and migrant workers without considering and reported them as their registered employees. Due to the same motivation, the agencies do not report those workers as well.

If we incorporate various sources of statistics into our analysis, it can be concluded that the effect of economic growth on employment expansion during the reform period is positive and spurred mainly by developments of non-public-owned sectors and/or informal sectors. Before SOE initiated its employment reform aiming to break the iron-rice-bowl in the late 1990s, the non-public-owned sectors had only marginally employed turned-over workers, in addition to absorbing migrant workers. It was only after the reform of urban employment system was accomplished and the “iron-rice-bowl” was broken, by and large, that labor allocation became mostly market-based. During this time the government implemented a lay-off subsidy program, built up an unemployment insurance system, a basic pension regime, and a minimum living standard program to protect urban workers, on the one hand, and liberalized labor market regulations to encourage labor mobility, on the other. As a result, the magnitude of urban employment has grown and the employment structure has diversified based on labor market mechanisms.

In most other countries, both developed and developing, the informal employment serves as double-edged weapon. On the one hand, by absorbing unemployed and underemployed laborers, informal sectors prevent them from falling into complete unemployment and hence absolute poverty. On the other hand, informal employment is characterized by lack of access to social security system and social protection network, still placing those laborers in a relatively vulnerable status. It is also the case for China. While informal sectors act as a pool absorbing cyclically surplus labor force, disjoining employment from growth fluctuation, employees in those sectors are poorly covered by social security programs. In addition to that, there is third function that informal employment performs in transition China. That is, the informal employment serves as a culture medium facilitating the transformation of labor allocation from planned-based mechanism to labor-based mechanism.

Mass unemployment in urban China is a phenomenon that emerged during the period of radical economic transition and structural adjustment in the late 1990s. Under the planning system and in the early time of reform, there was no overt unemployment, therefore, the official statistical system was unable to provide sufficient information to depict the situation of the labor market. The official indicator of unemployment is the registered unemployment rate, but it is widely believed to underestimate actual unemployment and therefore is questioned by domestic and international scholars (e.g. [Solinger, 2001b] and [UNDP, 1999]). Because registered unemployment does not cover those who were laid off and entitled to receive living allowance from the Reemployment Center (jointly funded by enterprises, central and local governments and insurance funds), this indicator fails to reflect the actual severity of urban unemployment. For example, between 1998 and 2000 when a large number of SOEs workers were laid off, the registered unemployment rate remained unchanged at 3.1 percent, whereas it increased to 3.6 percent in 2001, 4.0 percent in 2002, 4.3 percent in 2003, and 4.2 percent in 2004 and 2005 when the employment situation actually began to improve.

In 1996, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) started the household-based Sample Survey on the Population Changes (SSPC). Based on this survey, relatively accurate unemployment could have been calculated, because it follows ILO recommended definition of employment/unemployment.5 Though this calculation has never been done officially, one can still do an indirect estimation. From published data on components of population, we first estimate economically active population in urban areas by subtracting rural employment from the whole country’s economically active population6, then we take the difference between economically active population and employed population as unemployed population in urban areas. By definition, the ratio of urban unemployment over urban economic population is surveyed unemployment rate. Results are shown in Table 3.

Concerning the changes in labor market indicators presented in the table, we can summarize four facts. First, since the employment system reform began in the late 1990s, it is not that urban unemployment rate rises steadily, but that after reaching the peak of 7.6 percent in 2000, it actually tends to decline with fluctuations. Secondly, at the time when unemployment first appeared in the latter part of 1990s, there was not an unemployment insurance system available for laid-off workers. To avoid a possible social shock, a unique form of unemployment insurance was arranged by the Center for Reemployment Service, which operates at the enterprise level and provides the laid-off worker with basic living allowance and reemployment services. Since 2001, as the unemployment insurance system gradually matures, the government encourages the transformation of layoff workers from being protected under the reemployment service center to being covered by a scheme of unemployment insurance. As a consequence, while the numbers of laid-off workers decreased, the numbers of registered unemployed increased, but that does not necessarily indicate an aggravation of actual unemployment. Finally, the decline in the labor force participation rate can be attributed to discouraged workers’ effect – that is, being chronically unemployed, those who are willing to work but who lack the ability to find a job, remove themselves from the labor force (Wang and Cai, 2004). As the employment environment improves the labor force participation rate tends to increase, while expanded higher education enrolment has an effect to counteract it.

4. Changing labor market in China

Most developing countries experience a development process of a dual economy, characterized by (1) rural surplus labor as an endless and cheap labor supply for industrialization; (2) slow enhancement of wage and labor relations disfavoring ordinary workers; and (3) a persistent income gap between rural and urban areas. According to Lewis’ theoretical model (Lewis, 1954), this process continues until the Lewisian turning point is reached and the feature of unlimited labor supply disappears. International experiences suggest that at a certain stage of dual economy development, a country can form a productive structure of population by demographic transition – namely, adequate supply of labor and high savings rate, to fuel economic growth ( [Bloom and Williamson, 1997] and [Williamson, 1997]). Then the exhaustion of demographic dividend signifies the accomplishment of dual economy development.

In the process of demographic transition – from an initial pattern characterized by high death rate, high birth rate and low growth rate of population, through an interim pattern characterized by low death rate, high birth rate and high growth rate of population, to a final pattern characterized by low death rate, low birth rate and low growth rate of population, the time difference between the declines of birth and death rates leads to the formation of three phases of age structure characterized by high dependency ratio of children, high proportion of working population, and high dependency ratio of the elderly, respectively (Williamson, 1997). During the period between the earlier decline in death rate and the lagging decline of birth rate, the natural growth rate of population persistently climbs and the share of dependent youth in the total population increases accordingly. As the fertility rate begins to fall, the share of working-age population increases in a lagging pace of about 20 years time. The further drop in the fertility rate will lead to a slower growth in population and the population will become aging. Therefore, two sequential inversely U-shaped curves respectively for natural growth rate of population and for growth rate of working-age population can be expected if one tries to outline the path of demographic transition by time series.

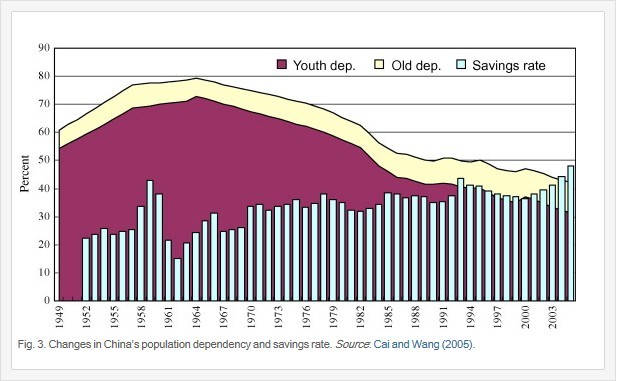

Because of the superposition between economic growth and demographic transition, the Chinese economic growth has fully utilized the demographic dividend during the transition. The large reservoir of and increase in working-age population are embodied in sufficient supply of labor and a low dependency ratio, which helps China hold a high savings rate (Fig. 3).7 Taking the drop in the total dependency ratio as a proxy for the increasingly advantageous population structure, in the period between 1982 and 2000, each one percent decrease in the dependency ratio led to a 0.115 percent of growth in per capita GDP. In 1982–2000, China’s population dependency ratio declined by 20.1 percent and contributed 2.3 percentage points to total 8.6 percent growth in per capita GDP – that is, the decline in total dependency ratio contributed 26.8 percent to the per capita GDP growth in the reform period (Cai and Wang, 2005).

As a joint result of the strict implementation of one-child policy and socio-economic development, China has completed a demographic transition from the interim pattern to the final pattern within approximately 30 years, a very short period of time when compared to most developed countries. The indication of this transition’s success is the decline in the total fertility rate from about 2.5 in the 1980s to a level below replacement since the late 1990s. The current fertility level in China is far lower than that in developing countries and parallels levels in developed countries in the mid 1990s. Usually, completing a demographic transition features not only an increase in the proportion of the elderly population, but also a decline in the proportion of the youth population as well as a rise followed by a fall in the dynamics of the working-age population percentage. As projected by the United Nations (2005), the proportion of China’s working-age population will continue rising until 2015, at which point it will begin to fall gradually. In absolute terms, China’s working-age population will peak at approximately one billion in 2015 or later before embarking upon a gradual decline. This projection sends an important message: in the near future, the size and proportion of China’s working-age population will change in ways different to those which we have long observed. Dynamically, the labor supply situation does not seem hopeful. This is apparently contradictory to the labor demand resulting from China’s sustained economic growth ( [Cai et al., 2006a] and [Cai et al., 2006b]).

The long-term demographics and the emerging trends in China’s labor market reinforce one another. Both the changes in population pattern and the diminishing surplus labor in rural areas described in previous sections imply that after a long-term development of dual economy, the feature of unlimited labor supply is vanishing – namely, the Lewisian turning point is bearing down upon the Chinese economy. As a milestone that divides development stages, this Lewisian turning point has important implications for labor market policies.

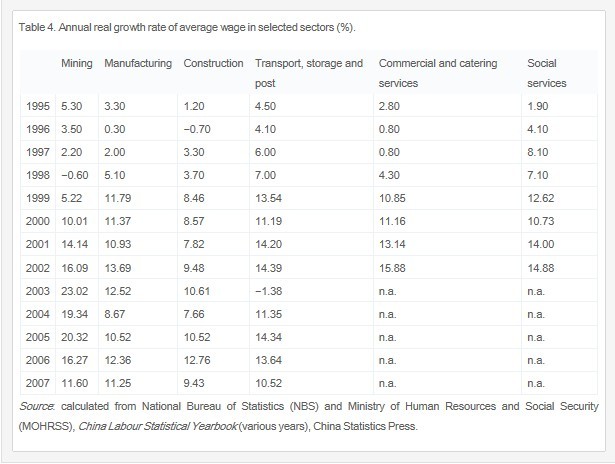

Under a dual economy, wage rates persist at a subsistence level until the expanding modern sector exhausts the surplus labor. As a consequence of emerging labor shortage, the competition for labor force inevitably leads to a rise of wages in the modern sector and in turn in agriculture, and the relationship between wage rate and productivity in agriculture becomes close to what economics expects (Watanabe, 1994). As early as in 2003, a shortage of migrant workers occurred in the Pearl River Delta region. As time goes by, the phenomenon of labor shortages has not gone away but has spread to the Yangtze River Delta region, and even to provinces in central China, from which migrant laborers are generally sent out. As a result of the emerging labor shortage, the average wage in urban sector has surged up dramatically. From all 16 sectors where data on average wages are available, we select 6 sectors in which ordinary unskilled workers are engaged and depict the changes in real average wages in these sectors (Table 4). It is apparent that nearly the real average wages in all those sectors have increased since the mid of 1990s.

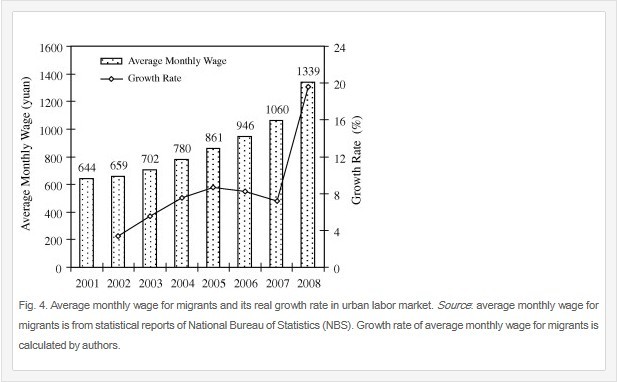

Though lagging behind, the wage rates of (unskilled) migrant workers increases as well. According to a survey conducted in five large cities8, between 2001 and 2005, hourly wages for workers in urban formal sector increased by 12.8 percent, that for urban workers in informal sector by 20.9 percent, and that for migrant employees increased by 31.9 percent. Compared with a long stagnation of migrants’ wage in the previous decade, the latest change is fundamental. According to National Bureau of Statistics, we can also see the significant increase of wage for migrants, which is shown is Fig. 4.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

During the reform period, China’s employment expansion has kept pace with its unprecedented economic growth though there are some fluctuations corresponding to economic ups and downs, while the dramatic changes in ownership and sectoral structure have been significantly reflected in the diversification of employment structure. The relatively radical reform of SOE’s employment system since the late 1990s led to labor market shocks manifested by mass lay-offs and unemployment. It sped up the process of labor market growth by eliminating institutional obstacles of labor integration, and created an ever large amount of employment opportunities for rural and urban labor force. As a result of economic reforms, opening-up and economic growth, and rural-to-urban migrants to help meet urban employment needs, urban employment has rapidly grown and thus the rural surplus labor force has been gradually absorbed. The Chinese economy is facing its era of labor shortage, which implies the vanishing of its duality.

As the trends of population structure and demand for and supply of labor show, the increase in labor costs authentically reflects the emerging labor shortage, a natural result of the change in relative scarcity of production factors. Therefore it does not weaken the competitiveness, but instead tends to enhance long-term competitiveness and sustainability of growth if it successfully pressures the economy to complete its transition from an inputs-driven growth pattern to a productivity-driven one. Furthermore, the current diminishing of labor supply is only an incremental phenomenon, which will not change the stock of labor force in China in the near future. In fact, China’s working-age population will remain in an annual growth rate of 0.7 percent between 2005 and 2015, and the large scale and proportion of the labor force in the total population will remain a feature of the Chinese population structure for quite a while. However, since the dual economy structure is not only a divide between traditional and modern economic sectors, but also a characterization of labor market segregation, the approaching Lewisian turning point also implies an urgent demand for institutional changes. That is, the conditions tend to be ripe for solving a host of problems such as imperfect migration of the rural labor force, income inequality and poverty, and insufficient guarantees for workers’ rights. It is critical for the Chinese government to precisely understand the changing nature of this development stage and to conform to its logic. This can be a turning point for adjusting policy orientations and resolving long-standing problems in economic development so that China’s economic growth can be sustained and the society can remain in harmony.

文章出处:Journal of Comparative Economics,Volume 38, Issue 1, March 2010, Pages 71–81