四、社会偏好的检验

在这部分内容中,我们最终回归到社会偏好理论的最初使命,即运用社会偏好理论去解释实验中发现的违背经济人假设的亲社会性行为时,常常面临这么一个问题,亲社会性行为可能受多重社会偏好的共同影响。具体来说,对于某种亲社会性行为的动机而言,利他偏好、互惠偏好以及差异厌恶偏好都可能对其进行解释。如何把这些不同类型的社会偏好区分以及分解呢?即当某种亲社会性行为可能受不同的社会偏好共同影响时,如何判定哪一种社会偏好能够较好地解释实验的悖论,也即如何在具体实验环境下分析和区别各社会偏好的异质性。下面,我们分别对最后通牒实验中响应者的拒绝行为、信任博弈实验中信任投资行为和可信任回报行为以及公共品实验中合作行为的社会偏好分解和检验问题进行总结。

(一)最后通牒实验中响应者拒绝行为的社会偏好检验

最后通牒实验是一个用来分析人们公平行为的经典实验。行为经济学家把公平分为动机公平与结果公平。这两种公平分别对应两种社会偏好,前者即互惠偏好,后者即差异厌恶偏好。从立足于这两种社会偏好的角度来说,对于最后通牒实验中响应者拒绝一个正的分配的原因有两种解释。第一种解释是响应者具备差异厌恶偏好,对于一个不公平的分配结果感到厌恶因此拒绝;第二种解释是响应者通过拒绝一个正的分配额从而达到对提议者“恶意动机”的惩罚。

Blount(1995)第一次指出了动机公平对人的决策行为的影响。举例来说,假设一个响应者面临一个(8,2)的分配方式,那么如果他拒绝了这种分配,正如上述所说,其原因不外乎两种:一是他可能反感别人用不公平的手段来对待他并从中获益;二是他可能仅仅是讨厌不等额的分配。如果他只是反感被不公平对待却不在意是否等额分配,那么若(8,2)的分配方案是由提议者提出的,则会遭到他的拒绝,但是他会接受由某种随机方法决定的或是由第三方(比如法院或规章制度)所裁决的一个同样的(8,2)分配方案。事实上,Blount(1995)发现,如果分配方案由某种随机方法决定而不是由提议者做出,那么此时响应者会设定一个较低的最小可接受出价。

但是,人的“动机”或者Rabin说所的“善意”和“恶意”是很难衡量或者说量化的,也很难寻找一个变量来替代它。这个难题可以在最后通牒实验的一系列修正型的设计中得到解决。实验经济学家注意到,备选方案在心理学意义上可以施加在已选方案上的影响给响应者发送一种动机上是否公平的信号,因此最后通牒实验中善意的体现是根据提议者的实际选择方案和可供选择的分配方案之间的比较来体现的。

在这一思路下,Nelson(2002)用一个标准最后通牒实验和删减版的最后通牒实验(truncated ultimatum game)进行了论证。在最后通牒实验中提议者的初始禀赋为20个美金进行任意的方案选择,而在删减版的最后通牒实验中,提议者的方案选择被限制了,即他最多给响应者只能分配4个美金的筹码。如果响应者仅仅是在乎结果的公平,即仅仅具备差异厌恶偏好,那么响应者在两个实验类型中对于(16,4)这样的分配方案的拒绝率应该是一致的。其结果显示对于一个(16,4)这样的分配方案,在参加标准最后通牒实验的44个人中只有17个实验参与者选择了接受,而在后者删减版的最后通牒实验中这一数目上升到了42个人。这一结果说明提议者分配方案的动机对响应者的决策行为产生了影响。

Falk等(2003)为了研究“动机”是否会对选择产生影响而采用了三个不同的最后通牒博弈实验。一个提议者可以选择(8,2)的方案并在(5,5)、(2,8)和(10,0)中任选一个作为备选方案。问题是在不同的备选方案情形下,响应者对于(8,2)的方案会如何做出反应。每一个备选方案都会使响应者对提议者的动机产生一个心理学上的评价,在备选方案为(5,5)时,提出方案(8,2)是相对不公平的,提议者的动机是自利的。在备选方案为(10,0)时,提出方案(8,2)表明提议者的动机是善意的,是想让响应者能获得一定收益而不是零。在备选方案为(2,8)时提出方案(8,2)说明提议者必须在两个不对称的方案中进行选择并且选择了对其较好的方案。Falk等(2003)的实验结果显示,在备选方案不同时,对(8,2)的拒绝频率是显著不同的。这说明“动机”因素在起作用。当备选方案是(5,5)时,有接近一半的响应者拒绝了(8,2)的方案。当备选方案是最自利的(10,0)时,只有10%的响应者拒绝了(8,2)的方案。而提议者似乎也预期到会出现这种在拒绝频率上的不同,因为当备选方案是等额的(5,5)时,只有三分之一的提议者提出了(8,2)的方案,但是在其他情形下却是大部分提议者提出(8,2)方案。由于忽略了备选方案的影响,因此仅用差异厌恶偏好作为效用函数的变量显然是不合适的。

Falk等(2003)和Nelson(2002)的实验设计在形式上虽然有所不同,但本质上都是通过两种分配选择方案来体现传达提议者行为动机的信号,从而研究该动机是否对响应者的行为决策产生影响,两者的结果也存在一致性,即对同一个分配方案会呈现出不同的拒绝率,这就论证了人们的行为决策确实受到他人行为动机的影响。

如果上述的文献从动机公平的角度分析其对人的行为决策的影响,那么Garrod(2009)的研究则主要分析结果公平(即差异厌恶偏好)对人的行为决策影响。Garrod(2009)采用一个由标准最后通牒实验、免惩罚博弈实验(impunity game)及保证博弈实验(garrateen game)组成的三合一UG实验,检验了差异厌恶理论对人的行为决策的影响。免惩罚博弈实验及保证博弈实验都是标准最后通牒实验的修正型实验。免惩罚实验在最后通牒实验的基础上扩大了提议者的权利,即响应者拒绝提议者的方案后提议者仍然可以获得提议方案中他的所得收益,而保证实验扩大了响应者的权利,即响应者拒绝提议者的方案后响应者仍然可以获得提议方案中响应者的所得收益,而此时提议者的收益为0。Garrod(2009)的三合一实验结果发现差异厌恶理论只能解释提议者的行为,而从响应者的行为来看,他们在免惩罚实验中倾向于放弃一个收益来扩大自己的劣势,即使这种放弃不能减少提议者的收益;而在保证实验之中,他们倾向于减少提议者的收益从而扩大自己的收益优势,即使响应者已经获得了一定的收益剩余。因此,从这两种实验的响应者行为来看,差异厌恶理论并不能进行解释。由此,Garrod(2009)认为,人们追求结果公平的假设并不能成立,因为差异厌恶理论并不能解释实验中超过一半的实验对象的行为决策。

一个有趣的研究是,Sutter(2007)着重研究了年龄因素对动机和结果公平的影响。他采用Falk等(2003)的实验设计,对儿童、青少年和大学学生三组群体分别进行了实验。他发现,相比较成年的大学生,儿童更加侧重于结果的公平,而前者更侧重于动机的公平。这从另外一个侧面说明年龄对世界观形成特别是程序正义的逐步加大对人的行为的影响。从三个年龄组的纵向比较来看,对(8,2)分配的拒绝率分别依次降低,说明动机在三个年龄组中均起显著影响。从三个年龄组的横向比较来看,大学生的拒绝率在所有四个MUG中均最低,说明年龄越小的实验对象越侧重于结果的公平。

总结来看,上述两种文献虽然研究的侧重角度不同,但得出的结论基本一致,即在最后通牒实验类型的研究中,动机公平对行为人的决策有着显著影响,而结果上的公平解释力不足。

(二)信任博弈实验中的信任行为和可信任行为的社会偏好检验

在Berg等(1995)的这个最初的信任博弈实验设计中,有没有可能在代理人没有回报的策略条件下,委托人依旧进行投资呢?在委托人和代理人拥有相同禀赋的信任博弈中,由于剔除了差异厌恶偏好的可能性,委托人对代理人选择一个大于0的投资水平的另外两种可能动机就是:互惠和利他。如果委托人具备较高的利他倾向,即使他没有互惠偏好,也可能做出信任的投资策略;而对于代理人的回报行为同样存在这样一个问题,即使代理人没有互惠偏好,他也有可能在利他偏好的动机下选择一部分筹码返还给委托人。Berg等(1995)没有把这两者因素区别开来,因此对信任水平和可信任水平的度量和检验就需要明确区分这背后的两种偏好因素。实际上,信任博弈实验是独裁者实验的一个变型,从投资人的角度来看,如果取消代理人回报的策略,那么它就是一个增值三倍的独裁者实验;如果给予独裁者实验中代理人回报的策略就变成了一个信任博弈实验;而从代理人的角度来看,其回报行为就是一个标准独裁者实验。正是信任博弈实验的结构与独裁者实验的结构存在的相同点,为信任博弈中委托人的投资行为和代理人的回报行为的社会偏好检验建立了基础。

Cox(2004)为此设计了一个三合一的信任实验(the triadic trust design),研究利他和互惠偏好对信任和可信任行为的影响。这三个实验分别为信任博弈实验、增值三倍的独裁者实验和修正型的标准独裁者实验。其中的信任博弈实验采用了Berg等(1995)的设计。在双方拥有相同10个筹码的初始禀赋时,当投资人选择投资X个筹码,代理人选择返还Y个筹码时,双方的收益分别为10-X+Y和10+3X-Y;而增值三倍的独裁者实验除了响应者没有权利返还的设计外其余与Berg等(1995)的设计相同,即独裁者和响应者的收益分别为10- 和10+3

和10+3 。其中,

。其中, 为独裁者给对方的分配额。在修正型的独裁者博弈中,双方的收益分别为10+3X-Y和10-X+Y,即双方收益与信任博弈中的收益刚好相反。对信任博弈实验委托人投资额与增值三倍的独裁者分配额进行,比较可以得出较为纯粹的信任及可能存在的利他偏好。从信任实验代理人的回报额和修正型的独裁者分配额的比较中,可以得出较为纯粹的可信任以及可能存在的利他偏好。Cox(2004)的实验数据表明,委托人的投资行为有一部分是由利他偏好导致的,而不是单纯受互惠偏好动机的影响。Cox(2004)的缺陷是没有估计这两种偏好的相对重要性,也没有分解个体特征和风险偏好对信任行为的影响,而且Cox(2004)的实验采用的是被试者间的实验设计(between-subjects design)。夏纪军(2005)运用Cox(2004)的实验设计在北京大学取得了20个实验样本数据,他们发现信任的投资行为和可信任的回报行为均受到利他偏好和互惠偏好的显著影响,但是利他偏好的影响程度均要大于互惠偏好,而这与Cox(2004)的数据刚好相反,显示出中国人的可信任结构具备建立在利他偏好基础上的特殊信任特征。

为独裁者给对方的分配额。在修正型的独裁者博弈中,双方的收益分别为10+3X-Y和10-X+Y,即双方收益与信任博弈中的收益刚好相反。对信任博弈实验委托人投资额与增值三倍的独裁者分配额进行,比较可以得出较为纯粹的信任及可能存在的利他偏好。从信任实验代理人的回报额和修正型的独裁者分配额的比较中,可以得出较为纯粹的可信任以及可能存在的利他偏好。Cox(2004)的实验数据表明,委托人的投资行为有一部分是由利他偏好导致的,而不是单纯受互惠偏好动机的影响。Cox(2004)的缺陷是没有估计这两种偏好的相对重要性,也没有分解个体特征和风险偏好对信任行为的影响,而且Cox(2004)的实验采用的是被试者间的实验设计(between-subjects design)。夏纪军(2005)运用Cox(2004)的实验设计在北京大学取得了20个实验样本数据,他们发现信任的投资行为和可信任的回报行为均受到利他偏好和互惠偏好的显著影响,但是利他偏好的影响程度均要大于互惠偏好,而这与Cox(2004)的数据刚好相反,显示出中国人的可信任结构具备建立在利他偏好基础上的特殊信任特征。

Ashraf等(2006)设计了一组由标准独裁者实验、增值三倍的独裁者实验及信任博弈实验组成的被试内设计(within-subjects design)来分解信任的决定因素。他们也把信任博弈分解为两个独裁者实验,一个是委托人对代理人的增值三倍的独裁者实验,另外一个就是代理人对委托人的标准独裁者实验。他们通过这两个独裁者实验分别测度委托人和代理人的利他偏好,在控制个体风险偏好及其他个体变量的条件下,实验数据分析表明信任投资行为同时受到互惠偏好和利他偏好的显著影响,而可信任的回报行为也同时受到互惠和利他偏好的显著性影响;这就表明无论是信任还是可信任,两者也均受到互惠和利他的双重影响,而且两种偏好在其中的影响程度并不一致,即信任的投资行为主要受互惠偏好的显著影响,而可信任的回报行为主要受利他偏好的显著影响。由此可见,相关的这些研究虽然都一致表明信任和可信任行为均受到利他和互惠偏好的双重影响,但是对这两种偏好的影响程度还存在着结果上的争议,直接影响到对信任结构的不同认识和分析,这就需要更多的实验数据来进一步探讨这个问题。

(三)公共品博弈实验中合作行为的社会偏好检验

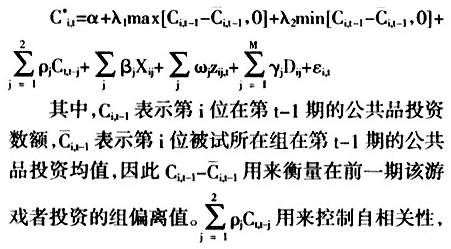

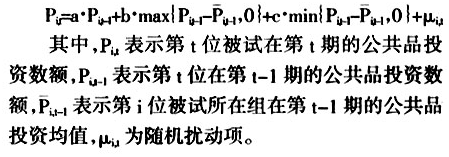

公共品博弈实验中合作行为(即投资行为)的社会偏好检验方法与最后通牒实验以及信任博弈实验中相应行为的社会偏好检验方法完全不同,因为公共品实验与这两种实验结构迥异,无法用别的实验对公共品实验进分解。Ashley等(2009)利用Isaac和Walker(1988)、Andreoni(1995)两个经典的公共品博弈数据对利他偏好(包括纯粹利他和光热效应理论)、互惠偏好和差异厌恶偏好首次进行了三种经典社会偏好在公共品博弈实验中的模型检验。他们的模型设置如下:

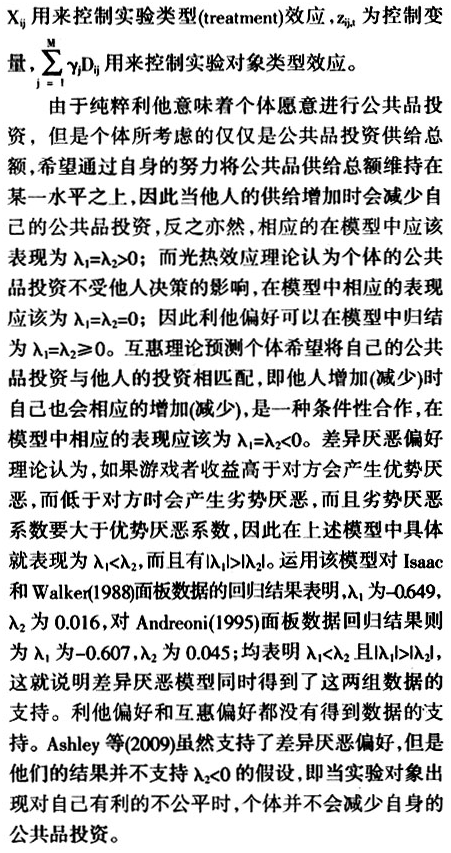

周业安、宋紫峰(2008)参照并简化了Ashley等(2009)的模型,他们运用在首都经贸大学24位被试公共品博弈数据的研究发现,互惠理论可以部分地解释显著存在的公共品供给,而纯粹利他理论和光热效应并没有得到数据的支持。他们的模型设计如下:

由于纯粹利他意味着个体愿意进行公共品投资,但是个体所考虑的仅仅是公共品投资供给总额,希望通过自身的努力将公共品供给总额维持在某一水平之上,因此当他人的供给增加时会减少自己的公共品投资,反之亦然,相应的在模型中应该表现为b=c>0;而光热效应理论认为个体的公共品投资不受他人决策的影响,在模型中相应的表现应该为b=c=0;互惠理论预测个体希望将自己的公共品投资与他人的投资相匹配,即他人增加(减少)时自己也会相应的增加(减少),是一种条件性合作,在模型中相应的表现应该为b=c<0。周业安、宋紫峰(2008)对8个公共品实验局的动态面板数据回归结果表明,有七个实验局中的b和c系数均为负值,而且所有显著的系数b和c均也为负值,这说明当被试发现自己的公共品投资数额高于(低于)组内平均值时,在下一期会减少(增加)自己的投资额,这就使得互惠理论得到了部分支持,而纯粹利他理论和光热效应理论没有得到数据的支持。

Ashley等(2009)与周业安和宋紫峰(2008)的结论不同。前者支持了差异厌恶偏好,后者支持了互惠偏好,因此有必要对该问题进行进一步讨论。互惠偏好和差异厌恶偏好的区别在于公共品博弈中的投资行为对这两种偏好的反应程度不同。互惠偏好意味着实验对象希望自己的公共品投资与他人的投资相匹配(matching),即他人增加(减少)时自己也会相应的增加(减少),这种匹配在这两种情况下是相当的;而差异厌恶偏好则认为,处于劣势不公平的反应要大于处于优势不公平的反应,即虽然两个系数可能均为负值,但是其绝对值大小不一。因此,这两个系数是否存在显著差异是区别这两种偏好的本质所在,互惠偏好意味着这两个系数不存在显著差别,而后者则相反。依据该标准,Ashley等(2009)与周业安和宋紫峰(2008)的研究结果仍不一致,而且关于第二个系数的符号问题也需要进一步进行检验,这就需要通过更多的公共品实验及数据对该问题进行探讨。

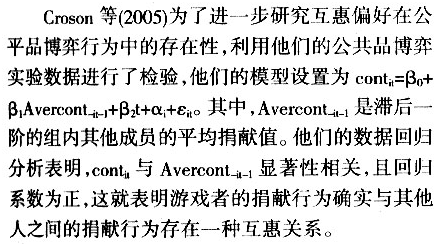

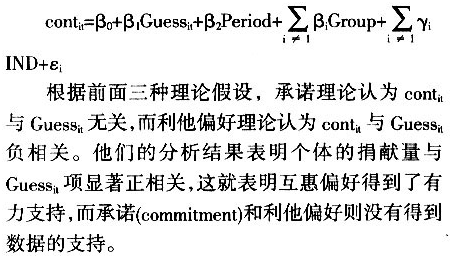

另一方面,为了比较互惠偏好、承诺理论(commitment rules)和利他偏好在公共品博弈中的重要性,Croson(2007)在其公共品博弈实验中设置了一个能测试出实验参与者信念预期的步骤,就是在公共品捐献前让游戏者猜想组内其他人的平均捐献值是多少,为了保证其真实效应,参与者的猜想如果正确可以获得额外的金钱奖励。因此,Croson(2007)的模型中多了这一项“猜想”变量。他们的模型设置如下:

五、小结

本文先简要介绍了社会偏好理论产生的一个背景,即实验中发现的大量亲社会性行为的存在,继而详细介绍了社会偏好的几个经典理论模型。围绕社会偏好理论,本文接下来详细讲述了其三个方面的内容,即社会偏好的测度、社会偏好的外溢以及社会偏好的检验。这三个问题也可以归结为社会偏好的三个性质问题,即社会偏好的可测度性、社会偏好的稳定性以及社会偏好的异质性。社会偏好的可测度性表明人的社会偏好是可以进行量化进而可以进行定量分析的,从而突破了以往经济学对公平、利他等概念在思辨意义上的分析。社会偏好的可测度性更为重要的意义在于说明人们的决策行为是可以预测的,正如Fehr和Schmidt(1999)所说,我们可以从一个实验中得到的数据估计出每一个被试效用函数的具体参数,从而可以进一步拿这些参数去预测这些被试在其他实验中的个体行为,这显然具有重要的理论意义。社会偏好的稳定性或者外溢性则进而说明实验室中测度的社会偏好是可信的,因为它可以外溢到现实生活中去,尽管实验室环境和现实环境有着天然的不同。社会偏好的异质性说明,人的行为和具体偏好的呈现依赖于特定的情境,实验环境作为人们现实生活的一个场景化的模拟和提炼,也会呈现出不同的社会偏好,而由于社会偏好依赖于特定情境下的异质性,这就需要社会偏好的具体运用时需先界定清楚具体的情境,并根据特定的情境选取不同的社会偏好模型,这才能更好地运用该理论去阐释传统经济学无法解释的经济现象和人类行为。

社会偏好理论使得主流经济学所忽视的关于善良怜悯、追求公平、互助友爱等人类特性第一次有了一个比较完整且规范的经济学分析框架,从而相应地为主流经济学无法解释的关于人类公平、信任和合作等问题提供了理论基础。它还原了人性规定的复杂性的真实,把人类社会生活的丰富属性完整地展现出来,而更难能可贵的是,社会偏好理论的各个模型在一定程度上是对社会生活中人类价值观多元化存在的认同。社会偏好理论确实也打破了经济人假设,不仅成功地解释了众多实验博弈的悖论,而且已经被应用到激励机制、企业制度改革、集体行动等各个领域,因此可以说社会偏好理论的形成及发展是经济学从“自利—竞争—一般均衡体系”向“他涉—合作—演化均衡体系”扩展的一个理论基石。特别是现代经济学前沿更多地开始关注合作现象,因为谋求合作和合作剩余可能是我们人类行为、人类心智与人类社会包括人类文化与人类制度共生演化的最终原因(叶航等,2005),那么就有必要超越经济人自利假设的局限,而社会偏好正为此奠定了一个理论上的分析基础。从某种程度来说,社会偏好可以说是人类合作形成的一个基石。因此它不仅是行为经济学和实验经济学的重大理论贡献,也是经济学理论发展进程中的一个重要转折点。社会偏好理论之所以成为行为经济学发展过程中比较成功的理论,一方面在于运用以实验经济学的突破为契机对经济人假设构成了系统性的反驳,更在于其理论的可塑性和实证的可操作性。从理论上来说它不仅超越了对经济人假设思辨层面的批判,而更侧重于学理上的建构。从实证上来说,它以实验室当中获得的大量实验证据作为强有力支撑,从而可以进行定量的规范分析。正是这两个方面使得社会偏好理论越来越受到主流经济学的重视,这已成为一个不争的事实。

在提及行为经济学和实验经济学的“范式革命”时,一个难以避免要提到而且也需要说明的是社会偏好与自利偏好两个概念之间的相互关系。如果仅仅从字面意义上来看,社会偏好(other-regarding preferences)与自利偏好(self-interest preferences)刚好是两个对立的概念,但是社会偏好理论并不否定自利偏好模型,实际上它是自利偏好模型的一个拓展,它们的最大共同点就是均建立在理性基础之上。⑨对此,Croson和G ther(2010)指出,任何一个经济学模型都存在模型的简洁性和应用性之间的“tradeoff”。自利偏好模型虽然应用很广,但是其逻辑性和科学性存在很多的缺陷;社会偏好的逻辑性和科学性更强,但是其应用范围也显然不及自利偏好模型。因此,它们实际上是一个相辅相成的理论体系。

ther(2010)指出,任何一个经济学模型都存在模型的简洁性和应用性之间的“tradeoff”。自利偏好模型虽然应用很广,但是其逻辑性和科学性存在很多的缺陷;社会偏好的逻辑性和科学性更强,但是其应用范围也显然不及自利偏好模型。因此,它们实际上是一个相辅相成的理论体系。

本文虽然围绕社会偏好理论按照其模型、测度、外溢性及检验等问题作了一个系统性的论述,但是由于社会偏好理论的文献很庞杂,受篇幅和精力所限,在这里我们没有对社会偏好的其他几个问题进行论述,其突出表现为社会偏好理论的具体应用以及社会偏好的神经元研究等问题,有兴趣的读者可以进一步阅读相关文献从而拓展对社会偏好理论的认识。⑩

注释:

①Camerer(2003)中的表2.2和表2.3详细列出了16篇最后通牒实验研究文献中的平均分配比和拒绝率,而其中的表2.5详细列出了Henrich等(2001)(该文可见中译文集,汪丁丁、叶航、罗卫东主编,2005年,《走向统一的社会科学:来自桑塔费学派的看法》,上海:上海世纪出版集团,第72-100页)15个小规模社会中的平均分配额和拒绝率,因此本文不再对最后通牒实验的相关文献基本数据进行罗列。

②他涉偏好(other-regarding preferences)是与社会偏好最相近的概念;“亲社会性偏好”(prosocial preferences)这个概念较为实质地概括了社会偏好正面积极的重要涵义,但它难免以偏概全,确实,社会偏好特别是其中的纯粹利他偏好、积极的互惠偏好等都反映了参与人亲社会性的一面,但比如其消极性的互惠偏好(或称破坏性互惠偏好更为形象)所产生的帕累托损耗行为则与所谓的“亲社会性”的原意背道而驰。有些学者如Sobel(2005)则喜欢称社会偏好为“互动偏好”(interdependent preferences)来强调社会偏好体现参与人与他人和社会互动的特性。

③值得注意的是,社会选择理论中的“社会偏好”作为“每个个体表达的偏好综合而成的整个群体的偏好”,其行为主体是整个社会,与行为经济学文献中作为个人的“社会偏好”有着明显的不同。

④该中译文可见凯莫勒、罗文斯坦、拉宾主编,《行为经济学新进展》,贺京同等译。北京:中国人民大学出版社,2010年,第348-382页。

⑤Camerer and Thaler(2003)对Rabin的学术贡献作了一个系统的介绍。

⑥Levine(1998)构造了一个与Rabin(1993)相近的互利模型,Sally(2001)则把“同情”引入了博弈模型并将其同情均衡与Rabin(1993)的公平均衡作了比较,发现囚徒困境的公平扩展型与同情扩展型存在诸多不同。

⑦有趣的是,为了比较这两个相近理论对实验数据的解释和预测力度,Engelmann和Strobel(2000)设计了一个实验,他们得出的结论是F&S模型更能对实验数据作出良好的预测。

⑧该中译文可参见凯莫勒、罗文斯坦、拉宾主编,《行为经济学新进展》,贺京同等译。北京:中国人民大学出版社,2010年,第318—347页。

⑨Rabin(2002)把心理经济学(psychological economics)按照对期望效用函数最大化问题即 π(s)U(x/s)的不同形式的拓展划分为三种类型,一是对偏好U(x/s)提出新的假定,二是对信念π(s)的重新构造,三是经济人不一定最大化其效用(有限理性),社会偏好理论实际上属于第一个类型。

π(s)U(x/s)的不同形式的拓展划分为三种类型,一是对偏好U(x/s)提出新的假定,二是对信念π(s)的重新构造,三是经济人不一定最大化其效用(有限理性),社会偏好理论实际上属于第一个类型。

⑩目前,社会偏好理论已被运用到不完全契约理论、委托代理理论、最优产权安排等领域,这方面的文献可参看Fehr and Schmidt(2003),Itoh(2004),Englmaier(2005)等的论述;而关于社会偏好的神经元研究可以参阅Camerer et al.(2005),de Quervain et al.(2004),Fehr et al.(2005),Fehr and Camerer(2007),Tricomi et al.(2010)以及叶航等(2008)等文献。

参考文献:

[1]克里斯汀·蒙特,丹尼尔·塞拉.博弈论与经济学(中译本)[M].北京:经济管理出版社,2005:314-326.

[2]凯莫勒,罗文斯坦,拉宾.行为经济学新进展[M].贺京同等译,北京:中国人民大学出版社,2010.

[3]汪丁丁,叶航,罗卫东.走向统一的社会科学:来自桑塔费学派的看法[M].上海:上海世纪出版集团,2005:72-100.

[4]夏纪军.中国的信任结构及其决定——基于一组实验的分析[J].财经研究,2005(3):39-51.

[5]叶航,汪丁丁,罗卫东.作为内生偏好的利他行为及其经济学意义[J].经济研究,2005(8):84-94.

[6]叶航,汪丁丁,贾拥民.科学与实证—— 一个基于“神经元经济学”的综述[J].经济研究,2007(1):132-142.

[7]周业安,宋紫峰.公共品的自愿供给机制:一项实验研究[J].经济研究,2008(7):90-104.

[8]Andreoni, J. Warm-Glow versus Cold-Prickle: The Effects of Positive and Negative Framing on Cooperation in Experiments[J]. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1995, 110(1): 1-21.

[9]Andreoni, J. Why Free Ride?: Strategies and Learning in Public Goods Experiments[J]. Journal of Public Economics, 1988, 37(3): 291-304.

[10]Andreoni, J. and Miller, J. Giving According to GARP: An Experimental Test of the Consistency of Preferences for Altruism[J].Econometrica, 2002, 70(2): 737-753.

[11]Ashley, R., Ball, S. and Eckel, C. Motives for Giving: A Reanalysis of Two Classic Public Goods Experiments[R]. School of Economic Political and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, CBEES Working Paper, 2009.

[12]Ashraf, N., Bohnet, I. and Piankov, N. Decomposing Trust and Trustworthiness[J]. Experimental Economics, 2006, 9(3): 193-208.

[13]Bahry, D., Kosolapov, M., Kozyreva, P. and Wilson, R. K. Ethnicity and Trust: Evidence from Russia[J]. American Political Science Review, 2005, 99(4): 521-532.

[14]Baran, N. M., Sapienza, P. and Zingales, L. Can We Infer Social Preferences from the Lab?: Evidence from the Trust Game[G]. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP7634, 2010.

[15]Bardsley, N. Experimental Economics and the Artificiality of Alteration[J]. Journal of Economic Methodology, 2005, 12(2): 239-251.

[16]Barr, A. Social Dilemmas and Shame-based Sanctions: Experimental Results from Rural Zimbabwe[R]. Working Paper, Centre for the Study of African Economies, 2001.

[17]Barr, A. Trust and Expected Trustworthiness: Experimental Evidence from Zimbabwean Villages[J]. The Economic Journal, 2003, 113(489): 614-630.

[18]Barr, A. and Kinsey, B. Do Men Really Have No Shame?[R]. Working Paper, Centre for the Study of African Economies, 2002.

[19]Becker, G. S. The Economic Approach to Human Behaviour[M]. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1976.

[20]Benz, M. and Meier, S. Do People Behave in Experiments as in the Field?: Evidence from Donations[J]. Experimental Economics, 2008, 11(3): 268-281.

[21]Berg, J., Dickaut, J. and McCabe, K. Trust, Reciprocity and Social History[J]. Games and Economic Behavior, 1995, 10(1): 122-142.

[22]Blanco, M., Engelmann, D. and Normann, H. T. A Within-subject Analysis of Other-regarding Preferences[J]. Games and Economic Behavior, 2010, Article in Press.

[23]Blount, S. When Social Outcomes Aren't Fair: The Effect of Causal Attributions on Preference[J]. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 1995, 63(2): 131-144.

[24]Bochet, O., Page, T. and Putterman, L. Communication and Punishment in Voluntary Contribution Experiments[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2006, 60(1): 11-26.

[25]Bolton, G. E. Comparative Model of Bargaining: Theory and Evidence[J]. American Economic Review, 1991, 81(5): 1096-1136.

[26]Bolton, G. E. and Ockenfels, A. ERC: A Theory of Equity, Reciprocity, and Competition[J]. American Economic Review, 2000, 90(1): 166-193.

[27]Brehm, J. and Rahn, W. M. Individual-Level Evidence for the Causes and Consequences of Social Capital[J]. American Journal of Political Science, 1997, 41(3): 999-1024.

[28]Buchan, N., Johnson, E. and Croson, R. Let's Get Personal: An International Examination of the Influence of Communication, Culture and Social Distance on Other Regarding Preferences[J].Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2006, 60(3): 373-398.

[29]Burks, S., Carpenter, J. and Verhoogen, E. Playing Both Roles in the Trust Game[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2003, 51(2): 195-216.

[30]Burns, J. Race and Trust in a Segmented Society[R]. Working Paper, University of Cape Town, 2006.

[31]Camerer, C. Progress in Behavioral Game Theory[J]. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 1997, 11(4): 167-188.

[32]Camerer, C. Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments on Strategic Interaction[M]. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2003, 11: 167-188.

[33]Camerer, C. and Fehr, E. Measuring Social Norms and Preferences Using Experimental Games: A Guide for Social Scientists[M]. In Foundations of Human Sociality: Economic Experiments and Ethnographic Evidence from Fifteen Small-Scale Societies, eds. Joseph Henrich et al., Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004: 55-95.

[34]Camerer, C., Loewenstein G. and Prelec, D. Neuroeconomics: How Neuroscience Can Inform Economics[J]. Journal of Economic Literature, 2005, 43(1): 9-64.

[35]Camerer, C. and Thaler, R. In Honor of Matthew Rabin: Winner of the John Bates Clark Medal[J]. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2003, 17(3): 159-176.

[36]Cardenas, J. C. En vos cofio: An Experimental Exploration on the Micro-foundations of Trust, Reciprocity and Social Distance in Colombia[R]. Working Paper, Faculty of Economics, Universidad de Los Andes, 2003.

[37]Cardenas, J. C. and Carpenter, J. Behavioral Development Economics: Lessons from Field Labs in the Developing World[J]. Journal of Development Studies, 2008, 44(3): 337-364.

[38]Capra, C. M., Lanier, K. and Meer, S. Attitudinal and Behavioral Measures of Trust: A New Comparison[R]. Department of Economics, Emory University Working Paper, 2008.

[39]Carpenter, J., Daniere, A. and Takahashi, L. Social Capital and Trust in Southeast Asian Cities[J]. Urban Studies, 2004, 41(4): 853-874.

[40]Carpenter, J. and Seki, E. Do Social Preferences Increase Productivity?: Field Experimental Evidence from Fishermen in Toyama Bay[J]. Economic Inquiry, 2011, 49(2): 612-630.

[41]Carpenter, J., Burks, S. and Verhoogen, E. Comparing Students to Workers: The Effects of Social Framing on Behavior in Distribution Games[M]. In J. Carpenter, G. Harrison and J. List(eds), Field Experiments in Economics (Greenwich, CT and London: JAI/Elsevier), 2005:261-290.

[42]Carter, M. and Castillo, M. An Experimental Approach to Social Capital in South Africa[R]. Working Paper, University of Wisconsin, 2003.

[43]Carter, M. and Castillo, M. Morals, Markets and Mutual Insurance: Using Economic Experiments to Study Recovery from Hurricane Mitch[M]. In C. Barrett, eds. The Social Economics of Poverty: On Identities, Communities, Groups and Network, New York: Routledge, 2005.

[44]Charness, G. and Rabin, M. Understanding Social Preferences with Simple Tests[J]. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2002, 117(3): 817-869.

[45]Charness, G. and Thaler, R. H. In Honor of Matthew Rabin: Winner of the John Bates Clark Medal[J]. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2003, 17(3): 159-176.

[46]Cherry, T. L., Frykblom, P. and Shogren, J. F. Hardnose the Dictator[J]. American Economic Review, 2002, 92(4): 1218-1221.

[47]Cox, J. How to Identify Trust and Reciprocity[J]. Games and Economic Behavior, 2004, 46(2):260-281.

[48]Croson, R. Theories of Commitment, Altruism and Reciprocity: Evidence from Linear Public Goods Games[J]. Economic Inquiry, 2007, 45(2): 199-216.

[49]Croson, R., Fatas, E. and Neugebauer, T. Reciprocity, Matching and Conditional Cooperation in Two Public Goods Games[J]. Economics Letters, 2005, 87(1): 95-101.

[50]Croson, R. and  , S. The Science of Experimental Economics[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2010, 73(1): 122-131.

, S. The Science of Experimental Economics[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2010, 73(1): 122-131.

[51]Danielson, A. and Holm, H. Do You Trust Your Brethren?: Eliciting Trust Attitudes and Trust Behavior in a Tanzanian Congregation[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 2007, 62(2): 255-271.

[52]Dannenberg, A., Riechmann, T., Sturm B. and Vogt, C. Inequity Aversion and Individual Behavior in Public Good Games: An Experimental Investigation[R]. Centre for European Economic Research(ZEW), Mannheim, Working Paper, 2007.

[53]de Oliveira, A. C. M., Croson, R. T. A. and Eckel, C. Are Preferences Stable Across Domains?: An Experimental Investigation of Social Preferences in the Field[R]. CBEES Working Paper #2008-3, 2009.

[54]D. J. F. de Quervain, Fischbacher, U., Treyer, V., Schellhammer, M., Schnyder, U., Buck, A. and Fehr, E. The Neural Basis of Altruistic Punishment[R]. Science, 2004,305(5688): 1254-1258.

[55]Duesenberry, J. Income, Saving and the Theory of Consumer Behavior[M]. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1949.

[56]Dufwenberg, M. and Kirchsteiger, G. A Theory of Sequential Reciprocity[J]. Games and Economic Behavior, 2004, 47(2): 268-298.

[57]Englmaier, F. A Survey on Moral Hazard, Contracts, and Social Preferences[M]. In Psychology, Rationality and Economic Behaviour: Challenging Standard Assumptions, Bina Agarwal and Alessandro Vercelli, eds. 2005.

[58]Engelmann, D. and Strobel, M. An Experimental Comparison of the Fairness Models by Bolton and Ockenfels and by Fehr and Schmidt[R]. Humboldt-Universit t zu Berlin, Working Paper, 2000.

t zu Berlin, Working Paper, 2000.

[59]Ensminger, J. Experimental Economics in the Bush: Why Institutions Matter[M]. In C. Menard(eds), Institutions, Contracts, and Organizations: Perspectives from New Institutional Economics, Edward Elgar, London, 2000, 158-171.

[60]Falk, A., Fehr, E. and Fischbacher, U. On the Nature of Fair Behavior[J]. Economic Inquiry, 2003, 41(1): 20-26.

[61]Falk, A. and Fischbacher, U. A Theory of Reciprocity[J]. Games and Economic Behavior, 2006, 54(2): 293-315.

[62]Falkinger, J., Fehr, E., G chter, S. and Winter-Ebmer, R. A Simple Mechanism for the Efficient Provision of Public Goods: Experimental Evidence[J]. American Economic Review, 2000, 90(1): 247-264.

chter, S. and Winter-Ebmer, R. A Simple Mechanism for the Efficient Provision of Public Goods: Experimental Evidence[J]. American Economic Review, 2000, 90(1): 247-264.

[63]Fehr, E. and Camerer, C. Social Neuroeconomics: The Neural Circuitry of Social Preferences[J]. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2007, 11(10): 419-427.

[64]Fehr, E. and Schmidt, K. A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation[J]. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1999, 114(3): 817-868.

[65]Fehr, E. and Schmidt, K. Theories of Fairness and Reciprocity: Evidence and Economic Applications[M]. In M. Dewatripont, L. P. Hansen, S. Turnovski, Advances in Economic Theory, Eighth World Congress of the Econometric Society, Vol. 1, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003: 208-257.

[66]Fehr, E. and List, J. The Hidden Costs and Returns of Incentives-Trust and Trustworthiness among CEOs[J]. Journal of the European Economic Association, 2004, 2(5): 743-771.

[67]Fehr, E. and G chter, S. Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments[J]. American Economic Review, 2000a, 90(4): 980-994.

chter, S. Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments[J]. American Economic Review, 2000a, 90(4): 980-994.

[68]Fehr, E. and G chter, S. Fairness and Retaliation: The Economics of Reciprocity[J]. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2000b, 14(3): 159-181.

chter, S. Fairness and Retaliation: The Economics of Reciprocity[J]. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2000b, 14(3): 159-181.

[69]Fehr, E. and G chter S. and Kirchsteiger, G. Reciprocal Fairness and Noncompensating Wage Differentials[J]. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 1996, 152(4): 608-640.

chter S. and Kirchsteiger, G. Reciprocal Fairness and Noncompensating Wage Differentials[J]. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 1996, 152(4): 608-640.

[70]Fehr, E., Fischbacher, U. and Kosfeld, M. Neuroeconomic Foundations of Trust and Social Preferences: Initial Evidence[J]. American Economic Review, 2005, 95(2): 346-351.

[71]Fisman, R. and Khanna, T. Is Trust a Historical Residue?: Information Flows and Trust Levels[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 1999, 38(1): 79-92.

[72]Fowler, J. Altruism and Turnout[J]. Journal of Politics, 2006, 68(3): 674-683.

[73]Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J. L., Savin, N. E. and Sefton, M. Fairness in Simple Bargaining Experiments[J]. Games and Economic Behavior, 1994, 6(3): 347-369.

[74]Friedman, M. Price Theory: A Provisional Text[M]. Aldine, Chicago, 1962.

[75]Garrod, L. Investigating Motives behind Punishment and Sacrifice: A Within-Subject Analysis[R]. Working Paper, ESRC Centre for Competition Policy, University of East Anglia, 2009.

[76]G chter, S. and Falk, A. Reputation and Reciprocity-Consequences for the Labour Relation[J]. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 2002, 104(1): 1-26.

chter, S. and Falk, A. Reputation and Reciprocity-Consequences for the Labour Relation[J]. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 2002, 104(1): 1-26.

[77]G chter, S., Herrmann, B. and Th

chter, S., Herrmann, B. and Th ni, C. Trust, Voluntary Cooperation, and Socio-economic Background: Survey and Experimental Evidence[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2004, 55(4): 505-531.

ni, C. Trust, Voluntary Cooperation, and Socio-economic Background: Survey and Experimental Evidence[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2004, 55(4): 505-531.

[78]Geanakoplos, J. D., Pearce, D. and Stachetti, E. Psychological Games and Sequential Rationality[J]. Games and Economic Behavior, 1989, 1(1): 60-79.

[79]Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D. L., Scheinkman, J. A. and Soutter, C. L. Measuring Trust[J]. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2000, 65(3): 811-846.

[80]Greig, F. and Bohnet, I. Is There Reciprocity in a Reciprocal-Exchange Economy?: Evidence of Gendered Norms from a Slum in Nairobi, Kenya[J]. Economic Inquiry, 2008, 46(1): 77-83.

[81]Güth, W., Schmittberger, R. and Schwarze, B. An Experimental Analysis of Ultimatium Bargaining[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 1982, 3(4): 367-388.

[82]Henrich, J. and Smith, N. Comparative Experimental Evidence from Machiguenga, Mapuche, Huinca and American Populations Shows Substantial Variation among Social Groups in Bargaining and Public Goods Behavior[M]. In J. Henrich, R. Boyd, S. Bowles, H. Gintis, E. Fehr and C. Camerer(eds), Foundations of Human Sociality: Economic Experiments and Ethnographic Evidence from Fifteen Small-scale Societies(Oxford: Oxford University Press), 2004, 125-167.

[83]Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H. and McElreath, R. In Search of Homo Economicus: Behavioral Experiments in 15 Small-Scale Societies[J]. American Economic Review, 2001, 91(2): 73-78.

[84]Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H., McElreath, R., Alvard, M., Barr, A., Ensminger, J., Henrich, N. S., Hill, K., Gil-White, F., Gurven, M., Marlowe, F., Patton J. and Tracer, D. Economic Man in Cross-Cultural Perspective: Behavioral Experiments in 15 Small-scale Societies[J]. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2005, 28(6): 795-815.

[85]Holm, H. J. and Danielson, A. Tropic Trust versus Nordic Trust: Experimental Evidence from Tanzania and Sweden[J]. The Economic Journal, 2005, 115(503): 505-532.

[86]Isaac, R. M. and Walker, J. M. Group Size Effects in Public Goods Provision: The Voluntary Contributions Mechanism[J]. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1988, 103(1): 179-200.

[87]Itoh, H. Moral Hazard and Other-Regarding Preferences[J]. The Japanese Economic Review, 2004, 55(1): 18-45.

[88]Johansson-Stenman, O., Mahmud, M. and Martinsson, P. Trust and Religion: Experimental Evidence from Bangladesh[R]. Department of Economics, G teborg University, Working Paper, 2005.

teborg University, Working Paper, 2005.

[89]Karlan, D. Using Experimental Economics to Measure Social Capital and Predict Financial Decisions[J].American Economic Review, 2005, 95(5): 1688-1699.

[90]Kennedy, B. P., Kawachi, I., Prothrow-Stith, D., Lochner, K. and Gibbs, B. Social Capital, Income Inequality, and Firearm Violent Crime[J]. Social Science and Medicine, 1998,47(1): 7-17.

[91]Keser, C. and van Winden, F. Partners Contribute More Than Strangers: Conditional Cooperation[J]. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 2000, 102(1): 23-39.

[92]Knack, S. and Keefer, P. Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff?: A Cross-Country Investigation[J].Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1997, 112(4): 1251-1288.

[93]Koford, K. Trust and Reciprocity in Bulgaria: A Replication of Berg, Dickhaut and McCabe(1995)[R]. University of Delaware Working Paper, 2003.

[94]Kohler, S. Difference Aversion and Surplus Concern: An Integrated Approach[R]. European University Institute, Florence, Working Paper, 2003.

[95]Kolm, S. C. The Theory of Reciprocity[M]. MacMillan Press Ltd, 2000, 115-141.

[96]Lazzarini, S., Artes, R., Madalozzo, R. and Siqueira, J. Measuring Trust: An Experiment in Brazil[J]. Brazilian Journal of Applied Economics, 2005, 9(2): 153-169.

[97]Lederman, D., Loayza, N. V. and Menendez, A. M. Crime: Does Social Capital Matter?[J]. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 2002, 50(3): 509-539.

[98]Leibenstein, H. Bandwagon, Snob, and Veblen Effects in the Theory of Consumers' Demand[J]. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1950, 64(2): 183-207.

[99]Leibbrandt, A., Gneezy, U. and List, J. Ode to the Sea: The Socio-Ecological Underpinnings of Social Norms[R]. Department of Economics, University of Chicago, Working Paper, 2010.

[100]Levine, D. Modeling Altruism and Spitefulness in Experiments[J]. Review of Economic Dynamics, 1998, 1(3): 593-622.

[101]Levitt, S.D. and List, J. A. What Do Laboratory Experiments Measuring Social Preferences Reveal about the Real World?[J]. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2007a, 21(2): 153-174.

[102]Levitt, S.D. and List, J. A. Viewpoint: On the Generalizability of Lab Behaviour to the Field[J]. Canadian Journal of Economics, 2007b, 40(2): 347-370.

[103]List, J. A. Young, Selfish and Male: Field Evidence of Social Preferences[J]. The Economic Journal, 2004, 114(492): 121-149.

[104]List, J. A. The Behavioralist Meets the Market: Measuring Social Preferences and Reputation Effects in Actual Transactions[J]. Journal of Political Economy, 2006, 114(1): 1-37.

[105]Loewenstein, G., Bazerman M. and Thompson, L. Social Utility and Decision Making in Interpersonal Contexts[J]. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1989, 57(3): 426-441.

[106]Marwell, G. and Ames, R. E. Experiments on the Provision of Public Goods. I. Resources, Interest, Group Size, and the Free-rider Problem[J]. American Journal of Sociology, 1979, 84(6): 1335-1360.

[107]Mosley, P. and Verschoor, A. The Development of Trust and Social Capital in Rural Uganda: An Experimental Approach[R]. Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series, SERP Number: 200501, 2005.

[108]Nelson, W. Equity or Intention: It Is the Thought That Counts[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2002, 48(4): 423-430.

[109]Nikiforakis, N. S. Punishment and Counter-punishment in Public Goods Games: Can We Still Govern Ourselves?[J]. Journal of Public Economics, 2008, 92(1-2): 91-112.

[110]Nikiforakis, N. S. and Normann, H. T. A Comparative Statics Analysis of Punishment in Public Goods Experiments[J]. Experimental Economics, 2008, 11(4): 358-369.

[111]Ockenfels, A. and Weimann, J. Types and Patterns: An Experimental East-West German Comparison of Cooperation and Solidarity[J]. Journal of Public Economics, 1999, 71(2): 275-287.

[112]Ortmann, A., Fitzgerald, J. and Boeing, C. Trust, Reciprocity, and Social History: A Re-examination[J]. Experimental Economics, 2000, 3(1): 81-100.

[113]Ottone, S. Fairness: A Survey[R]. Department of Public Policy and Public Choice, University of Eastern Piedmont "Amedeo Avogadro", Working Paper, 2006.

[114]Pollak, R. A. Interdependent Preferences[J]. American Economic Review, 1976, 66(3): 309-320.

[115]Rabin, M. Incooperating Fairness into Game Theory and Economics[J]. American Economic Review, 1993, 83(5): 1281-1302.

[116]Rabin, M. A Perspective on Psychology and Economics[J]. European Economic Review, 2002, 46(4-5): 657-685.

[117]Rustagi, D., Engel, S. and Kosfeld, M. Conditional Cooperation and Costly Monitoring Explain Success in Forest Commons Management[J]. Science, 2010, 330(6006): 961-965.

[118]Sally, D. On Sympathy and Games[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2001,44(1): 1-30.

[119]Schechter, L. Traditional Trust Measurement and the Risk Confound: An Experiment in Rural Paraguay[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 2007, 62(2): 272-292.

[120]Sobel, J. Interdependent Preferences and Reciprocity[J]. Journal of Economic Literature, 2005,43(2): 392-436.

[121]Stigler, G. J. and Becker, G. S. De Gustibus Non Est Disputandum[J]. American Economic Review, 1977, 67(2): 76-90.

[122]Sutter, M. Outcomes versus Intentions: On the Nature of Fair Behavior and Its Development with Age[J]. Journal of Economic Psychology, 2007, 28(1): 69-78.

[123]Tricomi, E., Rangel, A., Camerer C. and O'Doherty, J. Neural Evidence for Inequality-averse Social Preferences[J]. Nature, 2010, 463(7284): 1089-1091.

[124]Veblen, T. Essays in Our Changing Order[M]. Edited by Leon Ardzrooni, Viking Press, New York, 1934.

[125]Wilson, R. and Bahry, D. Intergenerational Trust in Transitional Societies[R]. Working Paper, Department of Political Science, Rice University, 2002.

[126]Wilson, R. and Sell, J. Liar, Liar: Cheap Talk and Reputation in Repeated Public Goods Settings[J]. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 1997, 41(5): 695-717.^